The Reading Selection from Infidel Death-Beds

[Religious Use of Dying Repentance]

INFIDEL death-beds have been a fertile theme of pulpit eloquence. The priests of Christianity often inform their congregations that Faith is an excellent soft pillow, and Reason a horrible hard bolster, for the dying head. Freethought, they say, is all very well in the days of our health and strength, when we are buoyed up by the pride of carnal intellect; but ah! how poor a thing it is when health and strength fail us, when, deserted by our self-sufficiency, we need the support of a stronger power…

Pictorial art has been pressed into the service of this plea for religion, and in such orthodox periodicals as the British Workman, to say nothing of the hordes of pious inventions which are circulated as tracts, expiring skeptics have been portrayed in agonies of terror, gnashing their teeth, wringing their hands, rolling their eyes, and exhibiting every sign of despair.

One minister of the gospel, the Rev. Erskine Neale, has not thought it beneath his dignity to compose an extensive series of these holy frauds, under the title of Closing Scenes. This work was, at one time, very popular and influential; but its specious character having been exposed, it has fallen into disrepute, or at least into neglect.…

[Psychological Aspect of Dying]

Throughout the world the religion of mankind is determined by the geographical accident of their birth. In England men grow up Protestants; in Italy, Catholics; in Russia, Greek Christians; in Turkey, Mohammedans; in India, Brahmans; in China, Buddhists or Confucians. What they are taught in their childhood they believe in their manhood; and they die in the faith in which they have lived.

Here and there a few men think for themselves. If they discard the faith in which they have been educated, they are never free from its influence. It meets them at every turn, and is constantly, by a thousand ties, drawing them back to the orthodox fold. The stronger resist this attraction, the weaker succumb to it. Between them is the average man, whose tendency will depend on several things. If he is isolated, or finds but few sympathizers, he may revert to the ranks of faith; if he finds many of the same opinion with himself, he will probably display more fortitude. Even Freethinkers are gregarious, and in the worst as well as the best sense of the words, the saying of Novalis is true—"My thought gains infinitely when it is shared by another."

But in all cases of reversion, the skeptic invariably turns to the creed of his own country. What does this prove? Simply the power of our environment, and the force of early training. When "infidels" are few, and their relatives are orthodox, what could be more natural than what is called "a death-bed recantation?" Their minds are enfeebled by disease, or the near approach of death; they are surrounded by persons who continually urge them to be reconciled to the popular faith; and is it astonishing if they sometimes yield to these solicitations? Is it wonderful if, when all grows dim, and the priestly carrion-crow of the death-chamber mouths the perfunctory shibboleths, the weak brain should become dazed, and the poor tongue mutter a faint response?

Should the dying man be old, there is still less reason for surprise. Old age yearns back to the cradle, and as Dante Rossetti says: —

"Life all past Is like the sky when the sun sets in it, Clearest where furthest off."

The "recantation" of old men, if it occurs, is easily understood. Having been brought up in a particular religion, their earliest and tenderest memories may be connected with it; and when they lie down to die they may mechanically recur to it, just as they may forget whole years of their maturity, and vividly remember the scenes of their childhood. Those who have read Thackeray's exquisitely faithful and pathetic narrative of the death of old Col. Newcome, will remember that as the evening chapel bell tolled its last note, he smiled, lifted his head a little, and cried Adsum! ("I am present"), the boy's answer when the names were called at school…

Supposing, however, that every Freethinker turned Christian on his death-bed. It is a tremendous stretch of fancy, but I make it for the sake of argument. What does it prove? Nothing, as I said before, but the force of our surroundings and early training. It is a common saying among Jews, when they hear of a Christian proselyte, "Ah, wait till he comes to die!" As a matter of fact, converted Jews generally die in the faith of their race; and the same is alleged as to the native converts that are made by our missionaries in India.

Heine has a pregnant passage on this point. Referring to Joseph Schelling, who was "an apostate to his own thought," " who deserted the altar he had himself consecrated," and "returned to the crypts of the past," Heine rebukes the "old believers," who cried Kyrie eleison ("Lord, have mercy in honor of such a conversion." "That," he says proves nothing for their doctrine. "It only proves that man turns to religion when he is old and fatigued, when his physical and mental force has left him, when he can no longer enjoy nor reason. So many Freethinkers are converted on their death-beds!… But at least do not boast of them. These legendary conversions belong at best to pathology, and are a poor evidence for your cause. After all, they only prove this, that it was impossible for you to convert those Freethinkers while they were healthy in body and mind."[1]

Renan has some excellent words on the same subject in his delightful volume of autobiography. After expressing a rooted preference for a sudden death, he continues: "I should be grieved to go through one of those periods of feebleness, in which the man who has possessed strength and virtue is only the shadow and ruins of himself, and often, to the great joy of fools, occupies himself in demolishing the life he had laboriously built up. Such an old age is the worst gift the gods can bestow on man. If such a fate is reserved for me, I protest in advance against the fatuities that a softened brain may make me say or sign. It is Renan sound in heart and head, such as I am now, and not Renan half destroyed by death, and no longer himself, as I shall be if I decompose gradually, that I wish people to listen to and believe."[2]

To find the best passage on this topic in our own literature we must go back to the seventeenth century, and to Selden's Table Talk, a volume in which Coleridge found "more weighty bullion sense" than he "ever found in the same number of pages of any uninspired writer." Selden lived in a less mealy-mouthed age than ours, and what I am going to quote smacks of the blunt old times; but it is too good to miss, and all readers who are not prudish will thank me for citing it. "For a priest," says Selden, "to turn a man when he lies a dying, is just like one that has a long time solicited a woman, and cannot obtain his end; at length he makes her drunk, and so lies with her." It is a curious thing that the writer of these words helped to draw up the Westminster Confession of faith.…

Professor Tyndall, while repudiating Atheism himself, has borne testimony to the earnestness of others who embrace it. "I have known some of the most pronounced among them," he says, "not only in life but in death—seen them approaching with open eyes the inexorable goal, with no dread of a hangman's whip, with no hope of a heavenly crown, and still as mindful of their duties, and as faithful in the discharge of them, as if their eternal future depended on their latest deeds."[3]

Lord Bacon said, "I do not believe that any man fears to be dead, but only the stroke of death." True, and the physical suffering, and the pang of separation, are the same for all. Yet the end of life is as natural as its beginning, and the true philosophy of existence is nobly expressed in the lofty sentence of Spinoza, "A free man thinks less of nothing than of death."

"So live, that when thy summons comes to join The innumerable caravan, which moves To that mysterious realm, where each shall take His chamber in the silent halls of death, Thou go not, like the quarry-slave at night, Scourged to his dungeon, but sustained and soothed By an unfaltering trust, approach thy grave, Like one who wraps the drapery of his conch About him, and lies down to pleasant dreams."[4]

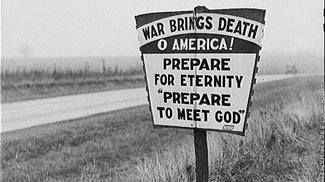

Religious sign on highway between Columbus and Augusta, Georgia, Library of Congress