Albert Camus, "Nobility of Soul"

Philosophy of Life

April 19 2024 02:35 EDT

Albert Camus, Sweden Postal Stamp (adapted)

SITE SEARCH ENGINE

since 01.01.06

Albert Camus, "Nobility of Soul"

Abstract: Camus finds meaning in life through the nobility or revolting against the absurd, i.e., acting in the face of meaninglessness.

- Explain in what way Camus believes that Sisyphus is representative of our own lives.

- What does Camus mean by the observation that "Sisyphus is the absurd hero"?

- Explain how "A face that toils so close to stones is already stone itself."

- Explain what Camus means when he writes, "There is no destiny that cannot be surmounted by scorn." In what way does scorn make Sisyphus superior to his fate?

- Explain how (and why) "…when the call of happiness becomes too oppressive," the rock becomes victorious. What does this insight mean for everyday life?

- What is the relation between happiness and the absurd? What does Camus mean by absurdity?

- Albert Camus (1913-1960) structured the basis of many of his works on

the notion of the absurd—the quest for meaning in a meaningless world.

- Camus represents the philosophy of existentialism (even though he

rejected that description of his writings in Les Nouvelles litteraires).

He considered himself more of a writer rather than of a philosopher.

- In any situation, no matter how confining, I still have choices. To

believe I do not have a choice in a situation, is, in effect, to

choose not to choose.

- Even if I am dying, I can choose how I die: in a panic or in acceptance, without forgiving or with forgiving, as an example for others or as sole concern for myself.

- If what Socrates says about tending my soul is understood, then although though I might be physically harmed by a specific decision, my soul can still be centered by that decision. There are no "have to's" in life as to what I must chose.

- This specific sense of "choice" implies that I must accept the consequences of my choices, even when those consequences are undeserved since the consequences of actions cannot be reliably foreseen. Yet, when I am self-directed and my soul is clear, the existentialist recognizes my anguish of taking personal responsibility for fortuitous consequences.

- As an existentialist, when I am self-directed and my soul is clear, I recognize my anguish of taking personal responsibility for the fortuitous consequences.

- In any situation, no matter how confining, I still have choices. To

believe I do not have a choice in a situation, is, in effect, to

choose not to choose.

- In the first sentence of Le Mythe, Camus says the most important

philosophical problem is the question of suicide. There is no intrinsic

explanation or meaning to life. (In the text, of course, Camus rejects

suicide on the basis that it results from the lack of moral strength

of character.)

- If we answer this question by what people do, rather than what they say, then the most important question is, by the same measure, the meaning of life.

- Saying it is a question of suicide, as Camus

does, is putting the question in terms of the alternative.

- Many people will give up their most cherished beliefs in order to go on living: e.g., Galileo, Peter the Apostle, a wife dedicated to a marriage, which is oppressive to her.

- Some people kill themselves because they judge it not worth the bother: e.g., a person over sixty-five whose spouse has just died; a teenager; a person who cannot live up to someone else's expectations.

- Others risk their own death for ideas which give them a reason to live: e.g., Socrates, a mountain-climber, a soldier, but more importantly, you, since essentially that is what your life becomes.

- Death is chosen when the individual is undermined and finds

himself in an unfamiliar world, faced with "the absurd."

- Consider for a moment the person who identifies worth of self with another person, a role, a profession, or a way of life. If the identification of self is broken, i.e., divorce, death, physical injury, being fired, or loss of interest, the meaning for self is lost.

- As Tolstoy wrote his essay described in a previous tutorial on, "A Confession: "I felt that what I was standing on had given way, that I had no foundation to stand on, that that which I lived by no longer existed, and that there was nothing left…" Tolstoy felt undermined.

- A person chooses death when life becomes too much: life is seen as "unfair" or arbitrary. There are too many demands, and no one can be counted on.

- Camus represents the philosophy of existentialism (even though he

rejected that description of his writings in Les Nouvelles litteraires).

He considered himself more of a writer rather than of a philosopher.

- Ideas of interest in Camus's Le Mythe de Sisyphe.

- Notes are arranged in response to the questions stated above in

reference to "The

Meaning of Life" from Le Mythe de Sisyphe translated by

Hélène Brown in Reading for Philosophical Inquiry.

- Explain in what way Camus believes that Sisyphus is

representative of our own lives.

- It should be obvious that we cannot control nature.

- If we seek to lose ourselves in the world, we are eluding. We are seeking a diversion from knowing ourselves or tending our own soul.

- Since the ego is completely different from the world, there are no absolutes to live up to. No one can really say, "You did a good job, kid." There is nothing objective to measure up to. Hence, you make the situation what it is by what you choose to make of it.

- Only by facing the absurd, can we act authentically; otherwise,

we elude and are controlled by other people and other

situations, as reflected in this popular quotation:

"I am not what I think I am. I am not what you think I am. I am what I have come to believe you think I am." This inauthenticity is the psychologist's notion of social reality. - Hence, at a minimum, we avoid wishful thinking and taking a convenient attitude (e.g., misfortune, accident, serious illness, death, always happens to the other guy.)

- You can never count on the consequences of your actions in the external world, yet you can always count on the motive or the thought accompanying the action—seize awareness of what you are.

- What does Camus mean by the observation that "Sisyphus

is the absurd hero"?

- We cannot be represented in the world; we are not what we do or how we appear to others. The world demands objectivity and materialistic precision which is not a characteristic of the values of consciousness.

- Consider, for example, that our university has no sanction for an "undecided" major. Administratively, this is not an adequate classification. Such persons are "in reality" only "undeclared majors." Indecision is not a property to be recognized in the world.

- Jean

Paul Sartre provides the example of the young man who puts

his hand on his first date's hand. She, who does not really know him

yet, must either leave her hand there or remove it. Either choice

reveals something not part of her consciousness. We are far

more than the limited opportunities present in the world.

- Consider, for a moment, how we do not "own" or

accept the truth of …

- our voice replayed on a tape recorder,

- our picture in a high school annual, or

- an overheard conversation about ourselves.

- We cannot be reduced to physical terms. These reconstructions are not what we are—so, in response to (x) above, "That doesn't sound like me," "That doesn't look like me," and "Let me tell you what really happened."

- Consider, for a moment, how we do not "own" or

accept the truth of …

- Thus, Sisyphus lives without endowed meaning and without hope for intrinsic meaning to his life. He knows that he cannot complete his task, yet the scornful suffering of the task provides purpose

- Explain how "A face that toils so close to stones

is already stone itself."

- Our fate lacks meaning when we continue to elude from our condition. The relationship between soul and the objective world is irrational. Sisyphus's face is stone when he loses himself (or sees significance) in the external world of objective events.

- The meaning of life of life cannot be found in the world around us—the impersonal thwarts human purpose.

Consider the daisy theory of a human being. When asked who

we are, we respond with our name, where we were born, what

jobs we do, and so forth. Yet we are not those things. That

is, we would still be who we are if our names were different,

our job was different, and so on.

Consider the daisy theory of a human being. When asked who

we are, we respond with our name, where we were born, what

jobs we do, and so forth. Yet we are not those things. That

is, we would still be who we are if our names were different,

our job was different, and so on.- Ofttimes, we are aware of a denseness or strangeness in the world, e.g., when we are ill.

- If we identify our meaning with the roles which bind our lives, we live in self-deception.

- Explain what Camus means when he writes, "There is

no destiny that cannot be surmounted by scorn." In what way does

scorn make Sisyphus superior to his fate?

- The nobility of revolting against the absurd is acting in the face of meaningless.

- I impose meaning on what I do. No one else can impose or choose meaning for me.

- From an objective view, all human activities, no matter how small or how important, are equal in how they are done. The "how" represents the meaning we impose on what we do.

- By simply enduring his task, which by its nature cannot be completed, Sisyphus finds happiness.

- When I, alone, impose meaning on what I do, I live authentically.

- Explain how (and why) "…when the call of

happiness becomes too oppressive," the rock becomes victorious. What

does this insight mean for everyday life?

- IF the hope or wish to complete the task of finally placing the rock at the top of the mountain is present, Sisyphus would become succumb to the punishment of the gods: the agony of recurring failures.

- The dejection from his recurrent inability to complete his purpose undermines the purported basis of his sought for happiness.

- Likewise, when we feel that we can finish a task or project and suppose that it is done and complete for all-time, then we are destined to be overcome by the flow of events. There are no end-points.

- The victory is in the struggle itself when we are aware that success is inapplicable and irrelevant in life. This realization leads to the heroic life.

- Camus writes, "Living the absurd" is a "permanent reflection."

- What is the relation between happiness and the absurd?

What does Camus mean by absurdity?

- Absurdity arises from the separation between you and the world. You are more than what you do. You are more than the opportunities provided by your environment. The range of choices presented in the world present no real choice, and there is no opportunity to be.

- Since we could never "be all that we could be," or realize our self in the world, we elude. Eluding is seeking diversions so that we will not have to face the fact of death, or for that matter, the possibility of authenticity.

- Recall Tolstoy's recounting of "The Well of Life" from the Mahabharata for insight into this state.

- If we pause to think about the situation, we are not "at

home" in the world. We constantly, but ineffectually, adjust

to not only nature but also to other people's expectations.

- Specifically, the impersonal nature of the universe clashes with the personality of human endeavor.

- This realization results in an "absence of hope." Our continual rejections from what we think should be, soon prevent our "bouncing back."

- Our eluding results in living as if we are unaware of our "beingness toward death."

- As we become aware of "the cruel mathematics which command

our condition," we realize we have only a limited time to

live.

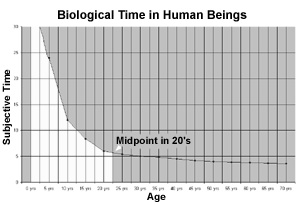

- Angelus Silesius writes, "You make the time, the senses are the clockwork." Biological time converts spatial difference into conscious duration.

- Several theories of aging rely on evidence that metabolic rates of organisms are inversely related to perceived time. In old age, when metabolism slows, subjective time speeds up. That's why grandparents often say, " It seems like yesterday that…"

- Roland Fischer writes, "…[Lecomte] du Noüy calculated the impression of ‘our passage’ in time for a twenty- and a fifty-year-old man to be four and six times faster than a five year-old child."

- A quick calculation from Lecomte du Noüy's data suggests the

sobering thought that perceived point where life is

half over for a seventy-year-old person would be in

the mid-twenties— as shown in the following

graph:

- Class exercise: Assume you will live to the age of 75. Calculate the number of seconds in your life. Now calculate and subtract from that total the number of seconds you have already lived. Finally. multiply the result by two-thirds in order to see the number of waking seconds left.

- What is even more alarming is the calculation of the number of weeks left to live. Assume that a person is 21 years old. Then, 52 weeks per year for the remaining 54 years yields 2,808 weeks left to live. Assuming one sleeps 8 hours per day, the awake-time remaining for a 21 year-old is only 1872 weeks.

- Absurdity is the presence of human consciousness, desire, and hope in the indifferent, uncaring reality of the external world. Revolting against the absurd is finding the courage to struggle and endure with the knowledge that success in what we do is impossible.

- Explain in what way Camus believes that Sisyphus is

representative of our own lives.

- Notes are arranged in response to the questions stated above in

reference to "The

Meaning of Life" from Le Mythe de Sisyphe translated by

Hélène Brown in Reading for Philosophical Inquiry.

- Albert Camus (1913-1960. The

significance of Camus's philosophy is discussed in this comprehensive entry by

Davis Simpson in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. His article is

a first, best Internet source on Camus.

- Albert Camus: The Absurd Hero. Bob Lane's essay honoring Camus on

the 25th anniversary of his death published in Humanist in Canada Winter,

1984/85 (Vol. 17, No. 4).

- Albert Camus. C.S.

Wyatt essays a biography, chronology, list of works as well as short

commentary, quotation, and notes on Camus's major works on his useful Website The Existential Primer.

- Camus and Sartre The

first chapter from Ronald Aronson's Camus and Sartre: The Story of a

Friendship and the Quarrel that Ended It is provided by the University of

Chicago Press.

- Banquet

Speech. The text of Albert Camus's speech is given in Stockholm on the occasion

of his receiving the Nobel Prize for literature in 1957.

- More on Albert Camus. Links

to articles and book reviews from the archives of The New York Times are listed.

Access requires free registration.

- Solitaire et Solidaire. Spike

Magazine interview by Russell Wilkinson with Catherine Camus focusing on her father's

book The First Man, a work first published in 1995, composed of the unedited and

unfinished manuscript found in the car crash in which Camus was tragically killed in

1960.

- Susan

Wolf on Meaning in Life. This interview on Philosophy Bites with Susan Wolf, University

of North Carolina, by David Edmonds and Nigel Warburton is a discussion of meaning

in life as one dimension of a good life. Wolf explains personal relationships

and vocational aspiration give meaning even though these factors might not involve

morality or happiness. Pursuits giving meaning in life must have both the qualities

of (1) being subjectively engaging and (2) objectively meaningful. Passion and

engagement in activity, as expressed in the Myth of Sisyphus is not enough for

meaning in life. Since some people, because of difficult living conditions, have no

meaning in life, Wolf notes that it is a somewhat of a luxury to have sufficient

resources for meaning to become possible in life.

“What should we want? And to reach what we want, what should we do? Men hesitate to answer. The idea of solving these problems without help fills them with anguish. They are still not used to being their own masters on earth; their freedom frightens them. here are many, therefore, who seek refuge in one of two conflicting attitudes, either of which can free man from himself: an intransigent moralism or a cynical realism. If they decide on moralism, they choose to obey an interior necessity, and enclose themselves in pure subjectivity; if on the other hand they choose realism they decide to submit to the necessity of things, and lose themselves in objectivity.” Simone de Beauvoir, “Moral Idealism and Political Realism” in Philosophical Writings ed. Margaret A. Simons (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2005) 177.

Relay corrections, suggestions or questions to

larchie at lander.edu

Please see the

disclaimer

concerning this page.

This page last updated 01/27/24

© 2006 Licensed under the GFDL