Ad Verecundiam (Argument from Authority) Explained with Examples

Contents

- The Argumentum ad Verecundiam Fallacy Defined and Explained

- The Basic Pattern of the Argumentum ad Verecundiam Scheme, the Conditions under which the ad Verecundiam is Fallacious, and Typical Example Analyzed

- The ad Verecundiam Distinguished from Other Informal Fallacies with Examples

- Some Varieties of ad Verecundiam Arguments Extracted and Explained from Various Readings

- The Proper Use of ad Verecundiam Arguments

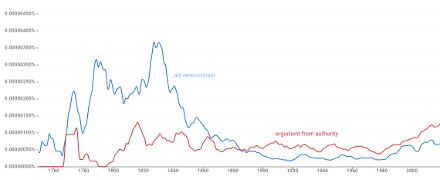

- The ad Verecundiam and the Argument from Authority Frequency of Use in Google Books Ngram Viewer

- Postscript Quotation for the Argumentum ad Verecundiam

- Links to Additional Examples and Online Practice Quizzes and with Suggested Solutions for the Argumentum ad Verecunciam

- Notes

The Argumentum ad Verecundiam Fallacy Defined and Explained

Argumentum ad Verecundiam Fallacy (argument from inappropriate authority): an appeal to the testimony of an authority outside of the authority's special field of expertise.

- From a logical point of view, anyone is free to express opinions or

advice about what is thought true; however, the fallacy occurs when the

reason for assenting to a statement is based on following the

recommendation or advice of an improper authority.

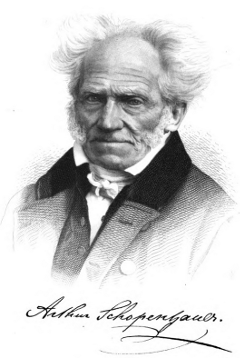

Arthur Schopenhauer cynically summarizes how the argument can be

effectively used to take advantage of opponents in argumentation:

Arthur Schopenhauer cynically summarizes how the argument can be

effectively used to take advantage of opponents in argumentation:

“[T]he argumentum ad verecundiam … consists in making an appeal to authority rather than reason, and in using such an authority as may suit the degree of knowledge possessed by your opponent. … The more limited his capacity and knowledge, the greater is the number of the authorities who weigh with him.[1]

Schopenhauer recommends citing obscure authorities to impress the unlearned. Logically, however, acknowledging authorities only carries some significance when the authority is an expert in the field under examination. Relevant and appropriate authorities frequently disagree on important issues.

- Although some logicians today use the Latin phrase

“argumentum ad verecundiam” (or often,

more simply, the phrase “ad verecundiam”

or “argument from authority”) as the name of a

fallacy, [2] historically

those phrases were mainly used to describe appealing to an authority's

judgment, relevant or otherwise, for use as evidence in an argument.

These terms were not initially used specifically to denote the fallacy of appealing to evidence provided by an irrelevant or ill-suited authority.[3]

- Different kinds of authorities are cited by logicians in

different kinds of ad verecundiam arguments:

experts in a particular field of knowledge (cognitive or epistemic authority): e.g., Bruce Catton, historian, an authority on the U.S. Civil War

prestigious or powerful individuals or institutions: e.g., Mahatma Gandhi, civil right activist, an authority on nonviolent resistance

governmental, legal or administrative officials: e.g., Hammurabi, King of Babylon, authority on legal code

social, family, religious, or ancestral heads: Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha, an authority on ethics

electronic knowledge resources — information accessed through information and communication technologies: e.g., Google Search, as an information search engine

- Many advertising campaigns are built on ad verecundiam

appeals. Popular sports figures, musicians, or actors endorse products of

which they have no special expertise, and, in this context, their celebrity

status is offered as a reason we should use those products.

- Even so, occasionally a movie star, for example, might also be an

appropriate authority in another field of expertise. For example,

former Hollywood actor and union leader Ronald Reagan could have been

relevantly quoted as a U.S. political authority at the time of his

California governorship or his U.S. presidency. Former Hollywood actor

and film director Paul Newman could have been quoted as an authority

on professional racing during his motorsports career as team owner and

race car driver. The reasoning of these individuals in those respective

fields would not ordinarily be open to the charge of an ad

verecundiam fallacy.

- Note also that an ad verecundiam argument is not

a deductive argument since its conclusion is

not claimed to follow with absolute certainty. Even a consensus of

reliable authorities can be mistaken about the subject matter in their

field of expertise at times.

- Ad verecundiam arguments are nonformal arguments

and are often considered inductive

arguments (i.e., arguments whose conclusions are claimed to

follow with probability). Ad verecundiam arguments

are not necessarily fallacious even if the claim by an

appropriate authority is subsequently found to be mistaken. (The

claim is considered to be wrong but not fallacious since a claim

considered in itself is not an

argument.[4]

- For example, in 1948, readers of Science News were invited

to buy a fluffy 80% cotton and 20% asbestos dish towel provided by the

Science Service

Program.[5] Concluding

that the towel would be safe and useful would not have been an

ad verecundiam fallacy at that time even though the

authority being relied upon, Science Service, a program of Science

News itself, was unaware asbestos can cause fatal illnesses.

The descriptions provided for the towel seemed probable at the time since

the health hazards of asbestos were not known.

- Ad verecundiam arguments are nonformal arguments

and are often considered inductive

arguments (i.e., arguments whose conclusions are claimed to

follow with probability). Ad verecundiam arguments

are not necessarily fallacious even if the claim by an

appropriate authority is subsequently found to be mistaken. (The

claim is considered to be wrong but not fallacious since a claim

considered in itself is not an

argument.[4]

- Even so, occasionally a movie star, for example, might also be an

appropriate authority in another field of expertise. For example,

former Hollywood actor and union leader Ronald Reagan could have been

relevantly quoted as a U.S. political authority at the time of his

California governorship or his U.S. presidency. Former Hollywood actor

and film director Paul Newman could have been quoted as an authority

on professional racing during his motorsports career as team owner and

race car driver. The reasoning of these individuals in those respective

fields would not ordinarily be open to the charge of an ad

verecundiam fallacy.

- In every case, the relevance or appropriateness of the

authority's expertise to the question at issue is the essential element

under consideration. Effective recognition and avoidance of this

fallacy is necessarily based on an adequate definition of an improper,

inappropriate or irrelevant authority. Developing criteria of relevance

for the extensive diversity of types of authorities proves to be

formidable.

- From a logical point of view, anyone is free to express opinions or

advice about what is thought true; however, the fallacy occurs when the

reason for assenting to a statement is based on following the

recommendation or advice of an improper authority.

The Basic Pattern of the Argumentum ad Verecundiam Scheme, the Conditions under which the ad Verecundiam Is Fallacious, and Typical Example Analyzed

The nonformal structure of the ad verecundiam fallacy, generally speaking, has this basic pattern:

informal guide to Ad Verecundiam Fallacy:

Authority L on subject X claims statement p.

Authority L's expertise is not relevant to subject X or statement p.

∴ p is claimed true.

The ad verecundiam argument is considered a fallacy if any of the following conditions are met:

(1) Expertise: The authority is not judged to be an acknowledged expert on subject under discussion by most other experts in that field.

(2) Statement Accuracy: The authority does not actually maintain the statement quoted or maintain any other statements provable from that statement.

(3) Statement Relevance: The statement is not relevant to, and not within the purview of, the subject under discussion.

(4) Substantiation: The authority cannot provide reasons, grounds, or evidence for the truth of the statement at issue.[6]

typical example of Ad Verecundiam Fallacy:

Researcher Linus Pauling winner of two unshared Nobel prizes, one for chemistry, another for peace, argued his daily use of vitamin C delayed the onset of his cancer by twenty years.

Obtaining Nobel Prizes in chemistry and for peace does not imply expertise in the prevention of disease.

∴ Vitamin C is effective in preventing cancer.

An authority is defined here as a person whose opinion or belief within a specific field of knowledge or practice is acknowledged, accepted, or entitled to be accepted as being non-biased and reliable. (Note the assumptive non-fallacious ad populum foundation of this definition.)

The Argumentum ad Verecundiam as Distinguished from Other Informal Fallacies with Examples

Historically, the ad verecundiam fallacy subsumes a variety of different kinds of fallacies of authority which are not often distinguished in logic textbooks.[7] These sub-fallacies often dovetail with other of the historically significant informal fallacies.

- The ad verecundiam fallacy in some cases overlaps

instances of the ad populum.

- Some ad verecundiam arguments are called the

“argument from prestige” since they are based on the belief

that respected people are not usually mistaken.

In cases where the belief or practices of an elite or privileged group of persons is being cited, the fallacy is frequently termed the “snob appeal” variety of the ad populum fallacy.

- Sometimes, the ad verecundiam and the

ad populum fallacies overlap

and so are not usually distinguished. For example, Schopenhauer recommends

the debate stratagem citing the “universal prejudice” of the

many as an authority in argumentation. He notes:

“There is no opinion, however absurd, which men will not readily embrace as soon as they can be brought to the conviction that it is generally adopted.”[8]

When viewed from a psychological perspective, members of groups often act to minimize internal conflict rather than risk disputes over what might be more effective practices.

- A fallacy example exhibiting such an overlap occurs in an argument

where the idealist historian Benedetto Croce distinguishes the eternal

idea of the “Holy” Inquisition

from its historical incarnation by the Catholic Church. The fallacy may be

identifiable as either an ad verecundiam or an

ad populum:

from its historical incarnation by the Catholic Church. The fallacy may be

identifiable as either an ad verecundiam or an

ad populum:

“The Inquisition must have been justified and beneficial, if whole peoples invoked and defended it, if men of the loftiest souls founded and created it severally and impartially, and its very adversaries applied it on their own account, pyre answering to pyre.”[9]

The reason this argument is fallacious is essentially based on the distinction between ethics and morals. In a word, ethics is a prescriptive discipline, whereas morality is a descriptive discipline. What is done is different from what ought to be done. What many persons think is right is not a sure sign of what is ethically right.

So, the ethical rightness of a practice is not merely determinable by the “authority” of numerous well-intended people over a period of time.

- Clearly, in other instances, citing the authority of a large group

of specified individuals need not be fallacious if the authority is an

appropriate, relevant authority.

For example, the following nonfallacious argument can be classified as either an ad verecundiam or an ad populum:“Singular as it may seem, trees do not die by the stroke [of lightning], but continue to grow on, unless shivered to pieces: the animal on which it falls (as appears by the testimony of such as have been struck and survived) neither sees, hears, nor feels anything; but is instantly deprived of sense.[emphasis added]”[10]

In this passage, the authority of the group of persons cited is relevant and so no fallacy occurs.

- Some ad verecundiam arguments are called the

“argument from prestige” since they are based on the belief

that respected people are not usually mistaken.

- The argumentum ad populum in some cases overlaps instances

of the argumentum ad baculum.

- With regulatory

authorities[11]

ad verecundiam arguments can be part of an argumentum

ad baculum in some situations:

“The U.S. Department of Transportation, in an effort to reduce the alarming increase in highway related deaths last year, announced Saturday that highway funds earmarked for bridge repair will be blocked in those states not proactively enforcing federal highway safety measures.”

However, in this case the authority is relevant and the threat is within the authority's purview so the argument is nonfallacious.

- With regulatory

authorities[11]

ad verecundiam arguments can be part of an argumentum

ad baculum in some situations:

- The ad verecundiam fallacy in some cases overlaps

instances of the ad populum.

Some Varieties of ad Verecundiam Arguments Extracted and Explained from Various Readings

Evaluate these passages excerpted from various readings for the presence of, and the fallaciousness of, an ad verecundiam argument:

- Specify if any of the following passages are ad

vericundiam arguments, and, if so, whether they are fallacious:

- “I find a second hopeful sign in the fact that many of the finest minds are to-day recoiling from the voice of absolute scepticism. …Prof. A. C. Armstrong, Jr., one of the most cautious students of philosophy, has noted with care the indications that ‘the day of doubt is drawing to a close.’… Romanes, the famous biologist, who once professed the most absolute rejection of revealed, and the most unqualified scepticism of natural religion, thinks his way soberly back from the painful void to a position where he confesses that ‘it is reasonable to be a Christian believer,’ and die in the full communion of the church of Jesus.’”[12]

The argument in this passage, if there is one, is that many intelligent persons are turning from scepticism to embrace religious faith. The writer's support for this thesis is to point out the two examples of Armstrong, a student of philosophy and Romanes, a biologist, both turning to faith.

At best, the argument is one of weak induction: two examples are given to support a generalization. The argument does not rely on the truth of the specific declarations of these two individuals; it relies only on the evidence of their being confirming instances of his thesis that many smart persons are turning to religion. The authorities' specific expertise may well be a sign “finest minds” are returning to religion but their specific expertise per se is not used as an appeal to authority to prove the conclusion that many intelligent people are turning to religion. Hence, the ad verecundiam argument is absent from this passage.

- “The United States policy toward mainland China in the 1980s was surely mistaken because Shirley MacLaine, a well-known actress at the time, emphasized she had grave misgivings about them.”[13]

An actress with no special qualifications in international relations or political science does not qualify as an experienced authority on the interactions between different countries in relation to their power and influence. So, the ad verecundiam argument is committed.

Background: Freeman Dyson is a theoretical physicist specializing

in quantum mechanics and astrophysics.

Background: Freeman Dyson is a theoretical physicist specializing

in quantum mechanics and astrophysics.

“Distinguished Scientist Freeman Dyson has called the 1433 decision of the emperor of China to discontinue his country's exploration of the outside world the ‘worst political blunder in the history of civilization.’”[14]

Although there is one one sentence in the passage, the implicit argument is we can be sure that China's prohibition of discovery in 1433 was the worst blunder in history because an eminent scientist said so. The conclusion is outside of Dyson's field of expertise, so as an argument, the ad verecundiam fallacy occurs. However, notice that even though such an argument would be fallacious, that fact does not thereby prove that the conclusion is false. Fallacious arguments sometimes have true conclusions.

- “Advocates for lifting age limits on Plan B [a.k.a., the morning-after pill], including Planned Parenthood president Cecile Richards, insist the pill is universally safe and, therefore, all age barriers should be dropped. From a strictly utilitarian viewpoint, this might be well-advised, but is science the only determining factor when it comes to the well-being of our children? Even President Obama, who once boasted his policies would be based on science and not emotion, has parental qualms about children buying serious drugs to treat a condition that has deeply psychological underpinnings.”[15]

President Obama's fields of expertise do not include medical ethics, so an irrelevant authority is being cited. Since the then President Obama is not an acknowledged authority for medical ethics, citing his opinion would not be logically relevant to the argument. As well, even as a legal authority, his expertise is dubious.

If relevant opinion were to be based upon experts in medical ethics, then those experts should be cited instead. The best that can be said is that President Obama is an intelligent man and so might have an informed opinion, but the implicit argument in this passage is an ad verecundiam fallacy.

- “Living organisms are the original control systems on this planet. As noted biologist Ernst Mayr puts it, ‘The occurrence of goal-directed [i.e., control] processes is perhaps the most characteristic feature of the world of living organisms.’”[16]

As Ernst Mayer is considered one of the last century's most noted evolutionary biologists and historian of science, the cited authority is relevant to the argument proposed. So the ad verecundiam fallacy does not occur.

Nevertheless, it's important to point out that Mayr's statement does not indicate that living organisms are the “original control systems on this planet.” Thus, the fallacy of ignoratio elenchi probably occurs since a characteristic feature of something is not necessarily the original feature of that thing. However, citing that fallacy as present in the passage excerpted might be hair-splitting.

- “Former U.S. President George W. Bush said that America would be much stronger if the people would return to traditional American values, and indeed he argues that we should. He says, ‘I am firmly convinced that our greatest problems today — from drugs and welfare dependency to crime and moral breakdown — spring from the deterioration of the American Family. Families must come first in America.’”[17]

Although it is to be expected that the president would be knowledgeable about the major problems of the United States, it is doubtful that Bush's expertise in the area of sociological causality is enough to consider him to be an authoritative source. The argument is a weak ad verecundiam and its fallaciousness is not clearly apparent.

- “A 1990 survey found 80 percent of economists agreed with the statement increases in the minimum wage cause unemployment among the youth and low-skilled. If you're looking for a consensus in most fields of study, examine the introductory and intermediate college textbooks in the field. Economics textbooks that mention the minimum wage say it increases unemployment for the least skilled worker.”[18]

Neither the ad verecundiam nor the ad populum fallacies occur. The individuals cited in the argument are economists and so are pertinent authorities on the minimum-wage issue.

The fact that a consensus of economists and of economic textbooks are mentioned in the premises is not fallacious since relevant economic authorities are being listed.

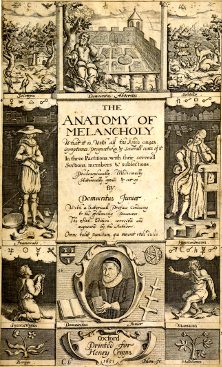

Backgound: Robert Burton, mentioned in the following argument,

was an 17th century Anglican clergyman, librarian, and writer.

Backgound: Robert Burton, mentioned in the following argument,

was an 17th century Anglican clergyman, librarian, and writer.

“These portrayals of women … in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries … regarded [women] as more easily able to convey a false emotional state, in their efforts to bewitch or betray unsuspecting men. … As the well-known English writer Robert Burton wrote of women in his Anatomy of Melancholy (first published in 1621), women are faithless and display false emotions in the calculated attempt to deceive men. He advised other men that when women protest their love, ‘believe them not.’”[19]

Burton's background as a scholar is insufficient to make him an authority on the understanding the sociocultural character of women of his age; consequently, this passage illustrates an ad verecundiam fallacy.

- ”To be right in everything, we ought always to hold that the white which I see, is black, if the Hierarchical Church so decides it.”[20]

The ad verecundiam fallacy occurs since the Hierarchial Church is not considered an authority on the subject of veridical perception (i.e., the question of whether our perceptions accurately reflect the external world).

- Background: Evangelist Billy Graham wrote the following implicit argument purporting to show the resurgence of Satanic religion in America.

Graham cites American novelist John Updike (who describes the decline of

religion in his novels), and Baptist minister Harvey Cox (who is Professor

of Divinity) in support of his thesis.

Graham cites American novelist John Updike (who describes the decline of

religion in his novels), and Baptist minister Harvey Cox (who is Professor

of Divinity) in support of his thesis.

“Arthur Lyons gave his book a title that is frighteningly accurate: The Second Coming: Satanism in America. This theme, which intellectuals would have derided a generation ago is now being dealt with seriously by such people as noted author John Updike and Harvard professor Harvey Cox.”[21]

Graham's argument is an attempt to bolster his thesis that the religion of Satan is making a reappearance in America culture — his claim is a sociological allegation. The novelist and the professor might possibly be considered authorities on Satanism but the sociological claim is outside the area of expertise of these authorities, so the ad vercundiam fallacy occurs.

- Although the following passages are considered fallacies in a popular logic

textbook, note why they are not fallacious:

- Background: The following passage is from Galileo's Two Dialogues Concerning Two New Sciences:

“But can you doubt that air has weight when you have the clear testimony of Aristotle affirming that all the elements have weight including air, and excepting only fire?”[22]

Strictly speaking this sentence is a question and, consequently, would not count as an argument.

If there is no argument, there is no fallacy. However, in context, the question might be interpreted as an argument of the following kind:“Aristotle affirmed these assertions.

At the time of writing, Aristotle was a proper and relevant authority in science, so at that time no fallacy would occur. Today, of course, Aristotle is no longer deemed an authority in natural science.

Aristotle is a relevant authority.

∴These assertions are true.”

Nevertheless, the passage quoted in the logic textbook was taken out of context. Galileo offers a supporting reason for fact that air has weight, and this next sentence was omitted from the exercise in the textbook:“As evidence of this he [Aristotle] cites the fact that a leather bottle weighs more when inflated than when collapsed.”

Since Aristotle gave evidence for his conclusion that air has weight, the argument does not depend upon his authority to substantiate this part of the argument. So the fallacy of accent (in this case more accurately termed “contextomy”) occurs: i.e. misquoting in such a manner that the facts are altered. Of course, this fallacy could not be identified unless the original source were consulted.

“In that melancholy book The Future of an Illusion, Dr. Freud, himself one of the last great theorists of the European capitalist class, has stated with simple clarity the impossibility of religious belief for the educated man of today.”[23]

“In that melancholy book The Future of an Illusion, Dr. Freud, himself one of the last great theorists of the European capitalist class, has stated with simple clarity the impossibility of religious belief for the educated man of today.”[23]

Mr. Strachey, the author of this argument, indicates his opinion of Freud's work and sums up its impact. Opinions might be right or wrong, but only arguments are properly described as “logically valid” or “fallacious.” It's likely no argument is present in this excerpt. However, the context of the passage might possibly have suggested the following argument:“Freud described how religious belief is wish fulfillment and no longer possible.

Freud is considered an authority on the psychology of religion (which would be included as part of the psychological nature of belief); however, he is probably not a proper authority on religious beliefs in and of themselves. However, religious beliefs per se are not at issue in the passage. In sum, the argument, if there is one, is not clearly fallacious, but it is not a particularly persuasive argument either. A substantial aspect of evaluation of this passage depends upon to what degree the term “educated man of today” is persuasively defined.

Freud is a proper authority on this.

∴ Freud's assertions are correct.”

- Specify if any of the following passages are ad

vericundiam arguments, and, if so, whether they are fallacious:

The Proper Use of ad Verecundiam Arguments

Proper experts and authorities render valuable opinions in their fields, and, ceteris paribus, their testimony should have direct bearing on the argument at hand — especially if we have no better evidence upon which to base a conclusion on securer grounds.

For example, Jeremy Bentham describes four important factors determining the cogency of an argument from authority,[24] and James A. Winans and William E. Utterback describe the legitimate use of authority in establishing the truth of the premises of an argument.[25] Even so, the specific relevance of the authority as well as the truth of the authority's testimony may become further points of contention.

- To qualify as an authority, the individual must be generally

recognized by peers in the same field or, at least, by peers who either

hold a similar view or peers who recognize the cogency of the point of

view being expressed.

- Examine, for yourself, why the condition of citing many

authorities in a field would not be an instance of the ad

populum fallacy.

The conclusions of relevant authorities are not to be accepted simply on the basis they stated something on, or about, a subject of their expertise, but rather on the basis their conclusions were reached by reason and experience.

An example of an argument where many authorities are invoked for support is pressed by Justice Jeremiah Black, U.S. statesman, lawyer, and judge in the mid-19th century. Justice Black denigrates “the Great Agnostic” Robert Ingersoll's arguments against the Christian doctrine of atonement as follows:

“The plan of salvation … could have been framed only in the councils of the Omniscient … [and] are not easily fathomed by finite intelligence. But the greatest, ablest, wisest, and most virtuous men that ever lived have given it their profoundest consideration, and found it to be not only authorized by revelation, but theoretically conformed to their best and highest conceptions of infinite goodness. Nevertheless, here is a rash and superficial man, without training or habits of reflection, who, upon a mere glance, declares that it ‘must be abandoned’ because it seems to him ‘absurd, unjust, and immoral.’”[26]

Able, wise, and virtuous authorities for either side of a religious issue can be marshaled. Putting aside Judge Black's ad hominem in the concluding sentence, we can see the appeal to nameless religious authorities provides little support for his argument. Authorities can be found for almost any controversial unfalsifiable issue we can name. What counts as proper support for a factual issue is authoritative, knowledgeable expertise based on reason and experience.- In sum, in the absence of other available evidence to us,

persuasive evidence of knowledgeable authority can be effective in

disputations.

- Examine, for yourself, why the condition of citing many

authorities in a field would not be an instance of the ad

populum fallacy.

- Nevertheless, in the final analysis of issues of critical importance, the

Royal Society motto should hold sway: Nullius in verba (“take no

one's word for it.)”[27]

Factual issues are not normally decided on the basis of which of various opposing legitimate authorities is the most illustrious. When authorities differ, arguments such as the following by the Roman forensic orator and philosopher Cicero are of minor consequence:“The discourse of Lucullus … moved me a good deal, being the discourse of a learned and ingenious and quick-willed man … But no doubt such authority as his would have influenced me a good deal, if you [Catulus] had not opposed your own to it, which is of equal weight. I will endeavour therefore, to reply to him after I have said a few words in defense of my own reputation, as it were.”[28]

Rather than evaluating the oratory of Lucullus on its own merits, Cicero judges its content in terms of how it is regarded by a hierarchy of authorities — his own authority judged by him as preeminent.

- To qualify as an authority, the individual must be generally

recognized by peers in the same field or, at least, by peers who either

hold a similar view or peers who recognize the cogency of the point of

view being expressed.

The ad Verecundiam Frequency of Use in Google books Ngram Viewer

FIG. 1. Historical Frequency of Use of ad Verecundiam and Argument from Authority in Google Books 1750-2019.

Postscript Quotation for the ad Verecundiam

postscript

“But man, proud man,

Dressed in a little brief authority,

Most ignorant of what he's most assured

…

Plays such fantastic tricks before high heaven

As make the angels weep”

(William Shakespeare, Measure for Measure Act II, sc. ii, ll 117-121.)

Links to Additional Examples and Online Practice Quizzes with Suggested Solution for the ad Verecundiam

Test your understanding of ad Verecundiam arguments which appear in the following quizzes:

Argumentum ad Verecundiam Examples Exercise: Rather difficult examples of ad verecundiam arguments for analysis in a self-grading quiz.

Other Quizzes on Fallacies for Self-Testing:

Fallacies of Relevance I

Fallacies of Relevance II

Fallacies of Relevance III

Notes

1. Arthur Schopenhauer, The Art of Controversy and Other Posthumous Papers trans. T. Bailey Saunders (London: Swan Sonnenschein, 1896), 36.↩

2. Charles Hamlin states:

“Historically speaking, argument from authority has been mentioned in lists of valid argument-forms as often as in lists of Fallacies.”

Charles Hamlin, Fallacies (London: Methuen Publishing, Ltd., 1970), 43.↩

3. In the late 17th century, John Locke first used the phrase argumentum ad verecundiam to describe one of four kinds of commonly used “assent producing devices”:

“Whoever backs his tenets with such authorities [‘men, whose parts, learning, eminency, power or some other cause has gained a name’], thinks he ought thereby to carry the cause, and is ready to style it impudence in any one who shall stand out against them. This I think, may be called argumentum ad verecundiam.”

John Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Knowledge, (London: Printed for G. and J. Offor et al., 1819), 253.

So Locke's coinage of the term was intended to describe the process of accepting the expertise of an eminent authority's judgment without further inquiry on the basis of modesty or respect for the authority's experience and learning. For him, argumentum ad verecundiam is a persuasive technique whereby one overawes by the use of authority without attending to reasons or evidence relevant to an inquiry.

In the mid-19th century, Schopenhauer writes,

”Those who are so zealous and eager to settle debated questions by citing authorities … will meet [any] attack by bringing up their authorities as a way of abashing him — argumentum ad verecundiam, and then cry out that they have won the battle.”

Arthur Schopenhauer, The Art of Literature, trans. T. Bailey Saunders (London: Swan Sonnenschien & Company, 1891), 69.↩

4. Other authors classify ad verecundiam arguments differently. Hamlin prefers to classify arguments from authority as “non-deductive” arguments rather than inductive arguments. He writes, “[T]here are clear cases of arguments that are non-deductive: inductive arguments, statistical or probabilistic arguments, arguments from authority …” C. L. Hamlin Fallacies (London: Methuen & Co. Ltd.: 1970), 249-250.↩

5. Janet Raloff, “Plumbing the Archives,” Science News 181 No. 6 (March 24, 2012), 21.↩

6. Douglas Walton's “crucial questions” for the defeasibility of the ad verecundiam are stronger than those recommended here. See Douglas Walton, Legal Argumentation and Evidence (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2002), 49-50 and Appeal to Expert Opinion (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2002), 211-225.↩

7. See, for example, Douglas Walton, Appeal to Expert Opinion: Arguments from Authority (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania University Press, 2010), 90.↩

8. Schopenhauer, Art of Controversy, 37.↩

9. Benedetto Croce Philosophy of the Practical: Economic and Ethic (1913; repr., Biblo & Tannen Publishers, 1969), 69-70.

The fallacy is presented in these texts (among others):

Daniel Sommer Robinson, Illustrations of the Methods of Reasoning: A Source Book in Logic and Scientific Method (New York: D. Appleton, 1927), 46.

Alburey Castell, Introduction to the Study of Argument and Proof (New York: Macmillan, 1935), 52.

Charles H. Patterson, Principles of Correct Thinking (Minneapolis, MN: Burgess, 1936), 85.

W. H. Werkmeister, An Introduction to Critical Thinking (Lincoln, NB: Johnsen, 1948), 60.

Richard E. Young, Alton L. Becker, and Kenneth L. Pike, Rhetoric: Discovery and Change (Harcourt, Brace & World, 1970), 261.

Nancy D. Simco and Gene G. James Elementary Logic (Wadsworth, 1983), 265.

Howard Kahane, Logic and Contemporary Rhetoric (Wadsworth, 1980), 49.

John Eric Nolt, Informal Logic: Possible Worlds and Imagination (McGraw Hill, 1984), 276.

S. Morris Engel, The Study of Philosophy (Collegiate Press, 1987), 132.

Irving M. Copi and Keith Burgess-Jackson, Informal Logic (Wadsworth, 1992), 136.

Douglas Walton, Appeal to Popular Opinion (Philadelphia: Pennyslvania State University Press, 2010), 45.

Irving M. Copi, Carl Cohen, Victor Rodych, Introduction to Logic 15th ed. (Routledge, 2018), 140.↩

10. Luke Howard, Seven Lectures on Meteorology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 95. doi: 10.1017/cbo9781139135467↩

11. Authority of command is discussed by Jean Goodwin, “Forms of Authority and the Real Ad Verecundiam, ” Argumentation Vol. 12 (1998), 267-280.↩

12. J. T. Plunket, “The Personal Christ, Gospel for Our Time,” in The Presbyterian Quarterly ed. G. B. Strickler, et al. (New York: A.D.F. Randolf Company, 1898), Vol. 12, 549.↩

13. Described in Charles Stuart Kennedy, Harry E. T. Thayer, Deputy Chief of Mission to George Bush, interview The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Library of Congress (November 19, 1990), 39.↩

14. Thomas Sowell, “A Historic Catastrophe” Index Journal 97 No. 148 (July 23, 2015), 6A.↩

15. Kathleen Parker, “Prude or Prudent?” Index-Journal

94 No. 4 (May 5, 2013), 11A.↩

16. Curran F. Douglass, Rationality, Control, and Freedom (London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015), 97.↩

17. George Bush, ”Remarks to the National Association of Evangelicals in Chicago Illinois, March 3, 1992,” Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: George Bush, 1992-3 Book 2 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1993), 368.↩

18. Walter Williams, “Higher Minimum Wages,” Index-Journal 94 No. 301 (February 27, 2013), 7A.↩

19. Deborah Lupton, The Emotional Self: A Sociocultural Exploration (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 1998), 109. doi: 10.4135/9781446217719↩

20. St. Ignatius, Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola trans. Father Elder Mullan (New York: P.J. Kennedy & Sons, 1914), 192.↩

21.Billy Graham, The Collected Works of Billy Graham (Inspirational Press, 1993), 14.↩

22. I. M. Copi, Introduction to Logic (New York: Macmillan, 1994), 135. The passage quoted is taken from Galileo Galilei, Dialogues Concerning Two New Sciences (New York: Macmillan, 1914), 77.↩

23. I. M. Copi, ibid, 133. ↩

24. Bentham writes:

“[T]he weight or influence to be attached to an authority … depends upon:

(1) the degree of relative and adequate intelligence of the person in question;

(2) the degree of relative probity of the same person;

(3) the nearness or remoteness between the subject of his opinion and the question in hand; and

(4) the fidelity of the medium through which such supposed opinion has been transmitted, including both correctness and completeness.”

Jeremy Bentham, Handbook of Political Fallacies, ed. H. A. Larrabee (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1971), 17-18.↩

25. Winans and Utterback point out that the argument from

authority is useful when matters of fact are beyond the knowledge of the

disputants and agreement is had as to the relevant authorities. Qualifications

of authority obviously depend upon “reputation for intellectual

competence” and “reputation for veracity.” James A. Winans

and William E. Utterback, Argumentation (New York: The Century

Company, 1930), 157-171.

In this, these authors follow the more subjective interpretation first presented

by the latter 18th century logician Isaac Watts who writes,

“When the Argument is fetch'd from the Sentiments of some wise, great, or good Men, whose Authority we reverence, and hardly dare oppose, it is called Argumentum ad Verecundiam as Address to our Modesty.”

Issac Watts, Logick, or, the Right Use of Reason in the Enquiry after Truth, 5th ed. corrected (London Printed for John Clark, et al., 1729), 311. I.e., Watts is suggesting the power of an argument is our diffidence to an acknowledged authority.↩

26. Chauncey F. Black, Essays and Speeches of Jeremiah S. Black (New York: D. Appleton, 1886), 9l.↩

27. “Science progresses by testing a hypothesis against the available evidence obtained through experiment and observation of the natural world. It is not based on the authority or opinion of individuals or institution. In fact the Royal Society motto ‘Nullius in verba’ can be roughly translated as ’take nobody's word for it.’” Parliament House of Commons: Science and Technology Committee, Peer Review in Scientific Publications (Great Britain: Stationery Office, 2011), 103.↩

28. Marcus Tullius Cicero, The Academic Questions: Treatise De Finnibus; and Tusculan Disputations, (London: George Bell and Sons, 1880), 180.↩

Send corrections or suggestions to

philhelp[at]philosophy.lander.edu

Read the disclaimer concerning this page.

1997-2024 Licensed under the Copyleft GFDL

license.

The GNU

Public License assures users the freedom to

use, copy, redistribute, and make modifications only if

they allow these same terms, with or without changes,

for their copies. Works for sale must link to a free copy.