The Uses of Language: Language Forms and Functions

Abstract: The forms and functions of language are discussed in terms of language forms (types of sentences) and language functions (informative, directive, and expressive uses). An understanding of the basic forms and functions is essential for the interpretation of meaning and intention in discourse.

Contents

Three Basic Functions of Language are the informative, expressive, and directive uses, and virtually all discourse is a mixture of these three functions, although several other ancillary uses are often noted.

Nevertheless few things are more subtle than the purposes to which language is put; few things have as many different uses.

Historically, language use has been investigated from many different standpoints: linguistics, anthropology, sociology, psychology, neuroscience, cognitive science, artificial intelligence, philosophy, literature, and philology. Many of these different viewpoints categorize different language uses from different conceptual foundations from those studied here.

Without a doubt, identifying just these three basic functions is an oversimplification, but an awareness of these functions is a good introduction to the complexity of language. Recognition of this complexity is essential for proper understanding and interpretation of ordinary language argumentation.

The primary use of language is both for communication in social interaction as well as for the formation and expression of personal thoughts.

The main reason we are inquiring into language use is that an acquaintance with the forms and functions of language will help enable us to logically resolve disagreements based on belief, attitude, or ambiguity.

The basic language functions in text are frequently determined by awareness of textual context of the sentences in a passage.

The Informative language function is essentially, the communication of information or ideas, factual reports, personal beliefs, and knowledge claims, but the informative language function also includes the communication of erroneous, mistaken, imaginative, and deceptive information.

The informative function usually occurs in statements which are sentences that express affirm, or deny an account, whether the account is factual, speculative, opinionated, false, or deceitful. Most informative sentences are declarative sentences with a subject-verb order such as “The wind howls,” but they can be present in any type of sentence: declarative, interrogative, imperative, or exclamatory.

This function is often used to describe the world or reason about it (e.g., whether a state of affairs has occurred or not, or what might or might not have led to a situation or event).

The following statements are some examples of predominantly informative content:

“[W]e know what we are, but not what we may be.” [Shakespeare, Ham.4.4]

“Fortune favors the bold.” [Virgil, Aen. 10.284]

“The immense prevalence of rice-eating impels the use of opium and narcotics.”[1]

These sentences often have a truth value of some kind; that is, the sentences are usually either true or false, probable of improbable. Hence, the ability to recognize the informative language function in discourse is requisite for the study of logic and argumentative discourse.

Expressive language function: reports feelings, attitudes, or emotion of the writer (or speaker), or of the subject, or evokes feelings in the reader (or listener). Many expressive sentences are exclamatory sentences which convey strong emotion and end with an exclamation point, and many are simply sentence fragments. E.g., “How nice!” or “Wow! Isn't that something!” Nonetheless, any type of sentence can be predominately expressive.

Poetry and literature are among the best examples, and ordinarily much of, perhaps most of, ordinary everyday discourse contains the expression of emotions, feelings or attitudes.

Two main aspects of this function are generally noted: (1) the evocation of emotion and (2) the expression of emotion.

Expressive discourse, as expressive discourse, is best regarded as neither true or false. For example, the well known initial sentence of Charles Dickens' A Tale of Two Cities invites us to experience imaginative lives beyond our own:

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times; it was the age of wisdom; it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness …”[2]

Whereas this stanza from William Blake's Songs of Innocence expresses pure delight:

“Pretty joy!

Sweet joy, but two days old.

Sweet joy I call thee:

Thou dost smile,

I sing the while,

Sweet joy befall thee!”[3]

Finally, note the lack of factual content in these expressive lines from Leo Tolstoy's War and Peace:

“Love is life. All, everything that I understand, I understand only because I love. Everything is, everything exists, only because I love. Everything is united by it alone.”[4]

Declarations such as these can only be assented to in attitude, not experiential agreement.

The assignment of truth values to such sentences is to miss the point of expressive discourse. Even so, there is an internal “logic” of “fictional statements.” (The logic of fictional statements an interesting area of study and is based upon logical coherence within the set of narrative statements.) Truth in fiction is usually only understood in a Pickwickian sense.[5]

The Directive language function occurs in language used for the purpose of causing (or preventing) overt action through requests or commands. Although the directive language use can appear in any type of sentence, imperative sentences are the most common.

Imperative sentences typically start with a verb and often the subject is an implied second-person pronoun“you” if the subject is not specifically stated. E.g., “Take care” or “Don't forget your lunch bag.”

The directive function is most commonly found in commands, instructions, and requests. Other uses include warnings, advice, invitations, and encouragement.

Directive language is not normally considered true or false (although various logics of commands have been developed).

Many examples of this function use the form of an imperative sentence. For example, Eleanor Roosevelt advised:

“Never allow a person to tell you ‘no’ who doesn't have the power to say ’yes.’”[6]

Other examples of the directive use of language might need interpretation if they are expressed in other than imperative sentences. For example, the Stoic Marcus Aurelius wrote:

“If thou art pained by any external thing, it is not this thing that disturbs thee, but thy own judgment about it [a]nd it is in thy power to wipe out this judgment now.”[7]

Marcus' intent is to advise that you can control your reactions to internal events but the occurrence of those external events, themselves, are beyond your control.

Mixed Functions in Discourse: Rarely does discourse serve only one function.

Even in a scientific treatise, discursive (logical) clarity is required, but, at the same time, ease of expression often demands some presentation of expressive attitude or feeling — otherwise the text would most likely not be engaging. In real world communication, these three functions are often commingled.

As an illustration of mixed discourse, consider this example from sales. Suppose you volunteer to canvass your neighbors for contributions to the Multiple Sclerosis Society. Several possible approaches can be taken.

You could explain the recent scientific breakthroughs in researchers' understanding of the disease (informative use) and then ask for a contribution (directive use).

You might make a moving appeal or emotional story of how a specific individual can be helped (expressive use) and then clearly ask for a contribution (directive use).[8]

You might just command it (directive use). (Needless to say, this approach is usually the least effective means of a contribution from most persons.

You could mention the promise of gene therapy techniques or the new disease-modifying therapies (informative use), then make a moving appeal (expressive use), and close by asking if they want to help (directive use). Most persons would not find information, by itself, a compelling reason to contribute.

Generally speaking, an appeal should begin with a compelling story (expressive) for emotional engagement, followed by a foundation of what specific effect a contribution will help make (informative), followed by a transparent request for a donation (directive).

Of course, such an appeal should be shaped to the prospective individual's situation. Often, a lengthy appeal is ineffective for time-constrained persons; sometimes, just making a moving appeal is the most effective means for a close neighbor. Other times, simply explaining surprising fresh research is effective for some educated persons. And very often, requesting a contribution is not necessary since a prospective contributor already surmises this step.

Ancillary Functions of Language: Several less prevalent uses of language deserve mention. These additional uses often overlap the primary functions.

The ceremonial function (sometimes termed “ritual language use”) is, in part, a confluence of the expressive and directive language functions. Some examples include:

“Dearly beloved, we are gathered here together to witness the holy matrimony of ….”

“Oyex, oyex, oyex“ is said in the U.S. Supreme Court to call the court in session. (The term derives from medieval courts in France and England.)

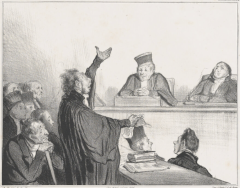

“May it please the court” as the traditional manner of making a request to a judge.”

“I do solemnly swear (or affirm) …” said before political oaths.”

Performative and phatic language functions (discussed below) are often present in the ceremonial uses as well.

- Performative utterances are a language use which does not just describe something but

actually accomplishes the action by statomg certain words. J.L. Austin, who first identified

this usage points out that a performative utterance is not truth function but is judged in terms

of its success.[9] For example, to say “I

do” in the marriage ceremony is the essential step in completing the marriage. It simply

wouldn't do for someone to claim later, “Hey, I was just teasomg.” Some other

examples Austin provides include:

“I name this ship the Queen Elizabeth — as uttered when smashing the bottle against the stem.”

“I bet you a sixpence it will rain tomorrow”[10]

Many other performative sentences include verbs such as “accept,” “apologize,” “congratulate,” and “promise” These words denote an action which is achieved by using the verb in the first person (i.e. using the word “I” as the subject term) — nothing more need be done to accomplish the action.

- Phatic language is a use of language first pointed out by anthropologist Bronisław

Malinowski[11] and further refined by linguist Roman

Jakobson[12] as a verbal means of human contact for

social bonding without the intent of communication of information. Sometimes termed “elevator

talk” or “small talk,” phatic language includes street-corner conversations

accomplishing a social task as well as a means of starting, sustaining, and ending conversations:

“Hello” or “How are you?”

“Um-hum” or “ I see,” or simply “O.K.”

“Bye” or “See you later.”

Note as well subtle transitions from phatic language to body language in different situations, for example, from speaking, “Hi” or “How are you?” to a nod, a tip of the hat, or a wave of the hand; all of which can accomplish a similar phatic function.

- Poetic language function:

Classical scholar John Conington describes the poetic function of language in prose as follows:

“[T]here are occasions where diffuseness is graceful, and a certain amount of surplusage may sometimes be admitted into harmonious prose for no better reason that to sustain the balance of clause against clause, and to bring out the general rhythmical effect.”[13]

For instance, suppose, as you are sitting quietly, a friend asks what you were thinking. Rather than saying matter-of-factly, “Sometimes I think about the past,” you can convey the same information with the poetic function of language and respond as Shakespeare once wrote:

“When to the sessions of sweet silent thought

I summon up remembrance of things past.” [Shakespeare, Sonnet 30, l. 1-2]

The use of poetic diction in ordinary prose sentences displays subtle evocative beauty in original expressive discourse.

-

Mixed Use Example: Most of the examples we have mentioned are not merely of academic interest. Here's a short example of the importance of language use and sentence structure from U.S politics:

- President Donald Trump challenged the outcome of the presidential election on January 6,

2021 in his “Stop the Steal” rally with these claims during his 70-minute speech:

“We will stop the steal … We will never give up. We will never concede. … If you don't fight like hell you're not going to have a country anymore. … Peacefully and patriotically make your voices heard. … We are going to the Capitol. …”[14]

When a speaker is charged “with inciting to riot,” the prosecution must prove the defendant intended to cause violence, and the speech is likely to cause violence.[15]

- Such evidence involves showing the defendant was using the directive language function of

language. In contrast, at trial, the defense would normally attempt to demonstrate that the

defendant was only freely expressing sentiment and opinion.

In the president's Senate trial, the defense team argued the phrases like “fight like hell” were simply rhetorical as shown by the presence of other phrases like “peacefully and patriotically.” The political composition of the Senate together with the later interpretation of intent resulted in an acquittal of the president.

In law courts, performative statements function like word-acts and upon occasion are not assessed by the court as hearsay testimony, but as “adduced evidence.”

- President Donald Trump challenged the outcome of the presidential election on January 6,

2021 in his “Stop the Steal” rally with these claims during his 70-minute speech:

The Forms of Language – Sentence Types: Although much discourse serves all three main language functions, those functions are not inextricably linked to the standard four types of English sentences (declarative, interrogative, imperative, and exclamatory).

The following chart displays how these specific types of English sentences can be used in certain circumstances for all three main functions: informative, expressive, of directive.

The point to be emphasized here is that any type of sentence can, in specific contexts, can be used for any sentence function.

Note that context of a sentence often determines the purpose to which the sentence is put. For example, the utterance, “The room is cool” might be used in different contexts as informative (as an observation of the temperature), as expressive (how chilly one feels at the moment), or even as directive (a “hint” to turn on the heater to someone).

Usual Function/

Sentence TypeInformative

ExampleExpressive

ExampleDirective

Exampleassertion /

declarativeThe room is cool. I had a nice time. I want some coffee question /

interrogativeBut isn't this room 22B? Isn't that great? Can't you help me? command /

imperativeRead pages 1-10 for the quiz. Have a nice day. Shut the window. exclamation /

exclamatoryThe universe is bounded! I'm really glad! It's late! Note that the sentence in the last cell of this table, “It's late!,” is used to convey the command to hurry up.

The Importance of Recognizing Language Functions in Discourse: The importance of our differentiation of functions is shown by realizing that the correct evaluation of the meaning and intention of a particular textual passage requires understanding the language functions in that passage.

The context of an utterance affects its meaning. A diner who says to a waiter, “I'd like a cup of coffee,” is not just reporting a psychological state of affairs.

That is, for the waiter to answer, “Speaking of things people like, I'd like a decent car” would be an inappropriate response.

Note that, ordinarily, a biology textbook is predominately informative, a work of fiction accentuates its expressive or imaginative elements, while logic or mathematics texts are mostly directive (since they instruct the proper ways to reason in those disciplines).

The British poet, literary critic, and semanticist, I.A. Richards once wrote:

“The understanding of the functions of language, of the many ways in which words serve us and mislead us, must be an essential aim of all true education. Through language all our intellectual and much of our social heritage comes to us. Our whole outlook on like, our behaviour, our character, are profoundly influenced by the use we are able to make of this, our chief means of contact with reality. A loose and insincere use of language leads not only to intellectual confusion but to the shirking of vital issues or the acceptance of spurious formulæ. Words were never a more common means than they are to-day of concealing ignorance and persuading even ourselves that we possess opinions when we are merely vibrating with verbal reverberations.”[16]

Conversational experience, perceptiveness of intentions, and awareness of dialogical context are essential to thoroughly understand different kinds of discourse. On many occasions, a particular sentence can encompass all three of the common functions of language.

“The most fundamental types of speech role, which lie behind all the more specific types that we may eventually be able to recognize, are just two: (i) giving and (ii) demanding. Either the speaker is giving something to the listener (a piece of information … or he is demanding something from him … Even these elementary categories already involve complex notions: giving means ‘inviting to receive’, and demanding means ‘inviting to give’. The speaker is not only doing something himself; he is also requiring something of the listener. Typically, therefore, an ‘act’ of speaking is something that might more appropriately be called an interact: it is an exchange, in which giving implies receiving and demanding implies giving in response.

“Cutting across this basic distinction between giving and demanding is another distinction, equally fundamental, that relates to the nature of the commodity being exchanged … This may be either (a) goods-&-services or (b) information. …

“If you say something to me with the aim of getting me to do something for you, such as ‘kiss me!’ or ‘get out of my daylight!’, or to give you some object, as in ‘pass the salt!’, the exchange commodity is strictly non-verbal: what is being demanded is an object or an action, and language is brought in to help the process along. This is an exchange of goods-&-services. But if you say something to me with the aim of getting me to tell you something, as in ‘is it Tuesday?’ or ‘when did you last see your father?’, what is being demanded is information: language is the end as well as the means, and the only answer expected is a verbal one. This is an exchange of information. These two variables, when taken together, define the four primary speech functions of offer, command, statement and question. [fn. … in extended descriptions of the system of speech function, each is the ‘root’ of a whole network of further speech-functional options …] These, in turn, are matched by a set of desired responses: accepting an offer, carrying out a command, acknowledging a statement and answering a question.”

M.A.K Halliday, An Introduction to Functional Grammar rev. by Christain Matthiessen 4th ed. (1985 New York: Routledge, 2014), 107-108.

Notes for Forms and Functions of Language

1. Friedrich Nietzsche, The Joyful Wisdom in The Complete Works of Nietzsche, Vol. 10, trans. Thomas Common (Edinburgh: T.N. Foulis, 1910), [III.145], 180.

2. Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1922), 15.↩

3. William Blake “Infant Joy,” in Songs of Innocence (New York: A.S. Barnes, 1961), 5.↩

4. Leo Tolstoy War and Peace, trans. Louise and Aylmer Maude (Reprint of J.M. Dent, 1932 by Standard Ebooks), Ch. 35, Sec. 16.↩

5. See, for example, Steven Schneider, “The Paradox of Fiction,” The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (accessed 2025-09-02). ↩

6. Eleanor Roosevelt quoted in Joslyn Pine, Wit and Wisdom of America's First Ladies (New York: Dover, 2014), 29.↩

7. Marcus Aurelius, The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, trans. George Long (London: Blackie & Son, 1910), 152. ↩

8. “[T]hat people are willing to expend greater resources to save the lives of identified victims than to save equal numbers of unidentified or statistical victims” has been described as the “identifiable victim effect.” Karen Jenni and George Loewenstein, “Explaining the Identifiable Victim Effect,” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 14 no. 3 (1997), 235. doi:10.1023/A:1007740225484 The emotion-first story told to grab the attention of a potential donor is sometimes sardonically described as “the emotional hook” in charity funding and marketing.↩

9. Austin's terms for the success or non-success of performative utterances is the evaluation as to whether it is “felicitous” or “infelicitous.” J.L. Austin, How to Do Things with Words 2nd. ed. (Harvard University Press, 1975), 5.↩

10. Austin, 5. John R. Searle extends and improves Austin's work on speech acts in his Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language (1969 Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).↩

11. Malinowski defines phatic communication as language which “ serves to establish bonds of personal union between people brought together by the mere need of companionship and does not serve any purpose of communicating ideas.” Bronisław Malinowski, “The Problem of Meaning in Primitive Language” in C.K.Ogden and I.A. Richards, The Meaning of Meaning 2nd ed. (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1927), 315.↩

12. Jacobson in his presentation of the phatic function quotes the beginning of a short story by the humorist Dorothy Parker as an example of a phatic exchange:

Roman Jacobson, Metalanguage as a Linguistic Problem,” Roman Jakobson Selected Writings (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1962), 115.↩“Well!” the young man said.

“Well!” she said.

“Well, here we are,” he said.

“Here we are,” she said. “Aren't we?”

“I should say we were,” he said. “Eeyop. Here we are.”

“Well!” she said.

“Well!” he said.

[Dorothy Parker, “Here We Are,” in The Collected Stories of Dorothy Parker (Ashford, UK, 2022), 43.]

13. John Conington, “Advantages of Prose,” in Miscellaneous Writings ed. J. A. Symonds (London: Longmans, Green, 1872), I: 107.↩

14. Brian Naylor, “Read Trump's Jan. 6 Speech, A Key Part Of Impeachment Trial.” NPR (February 10, 2021) (accessed 2025-11-02).

15. “[T]he principle that the constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not permit a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.” Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444, 447, 89 S.Ct. 1827, 1829, 23 L.Ed.2d 430 (1969).↩

16. I.A. Richards, “The Future of Grammar,” Cambridge Magazine, Vol. 10 no. 1 (Summer, 1920), 56. Note Richards' use of the poetic function of language in the last phrase of this quotation. ↩

Readings on Forms and Functions

Frederick Ferré, “The ‘Family Background’ of Linguistic Philosophy,” in Language, Logic, and God (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1961), 1-7.

This short summary of the rise of the importance of language in 20th century philosophical inquiry recounts how the dominant function of philosophy became the analyses of the meaning of language. Philosophers recognized that their discipline hereafter could provide neither empirical nor transcendent knowledge.

C.K. Ogden and I.A. Richards, The Meaning of Meaning 2nd ed. (Harcourt, Bracce, & Company, 1927), 226-242.

This work is perhaps the first accomplished recognition of the many functions language performs. The authors recognize five functions of language and illustrate a variety of examples from scholarly works of literature, psychology, and philosophy.

Read the disclaimer concerning this page.

1997-2025 Licensed under GFDL and Creative Commons 3.0

The “Copyleft” copyright assures the user the freedom to use,

copy, redistribute, make modifications with the same terms.

Works for sale must link to a free copy.

The “Creative Commons” copyright assures the user the freedom

to copy, distribute, display, and modify on the same terms.

Works for sale must link to a free copy.