![]()

|

|

|

| Quizzes |

| Tests |

| FAQ |

| Links |

| Search |

| Readings |

| Syllabus |

Ad Populum:

Ad Populum:

Appeal to Popularity

Examples Self-Test

with Answers

Abstract: Ad populum (appeal to popularity) and related fallacy examples are analyzed for credibility in a self-scoring quiz.

Ad Populum Examples Exercise

Ad Populum Fallacy Practice Directions:

(1) Study the features of the argumentum

ad populum from this web page: Ad

Populum.

(2) Read and analyze the following passages.

(3) Explain with a sentence or two as to whether or

not you judge an ad populum fallacy to be present.

(4) Check your answer.

- “To his dying day, Governor Marvin Mandel will never understand what was wrong in accepting more than $350,000 worth of gifts from wealthy friends who happened to engage in business ventures that benefited from his gubernatorial influence. The governor has lots company … And to a man they have cried in bewilderment that ‘everybody does it,’ that politics survives on back scratching.”[1]“The argument present in this passage is essentially as follows:

Businessmen often present gifts to public officials.

Simply because many politicians accept gifts from businessman does not thereby make the practice acceptable. The ad populum (bandwagon) fallacy is used.

Public officials, in return, help businesses.

∴ Public officials' acceptance of gifts is an acceptable practice. - St. Augustine wrote, “For such is the power true Godhead that it cannot be altogether and utterly hidden from the rational creature, once it makes use of its reason. For with the exception of a few in whom nature is excessively depraved, the whole human race confesses God to be author of the world.”[2]The ad populum fallacy: Augustine argues that since almost everyone thinks that God created the world, it reasonably follows that God did create the world. Again, simply because everyone believes something is the case, it does not logically follow that that it is the case. Note, as well in Augustine's argument, the ad hominem implications of the phrase “a few in whom nature is excessively depraved.”

- “A majority held in restraint by constitutional checks and limitations, and always changing easily with deliberate changes of popular opinions and sentiments, is the only true sovereign of a free people.”[3]Although a majority of persons is referenced in this passage, there is no argument present — just an assertion describing the government of the U.S. Consequently, no fallacy occurs.

- Thomas Collins Simon attributes this argument to philosopher Thomas Reid:

“If all that the senses present to the mind is sensations, Berkeley must be right — but Berkeley assumed this premiss without any foundation or any proof of it. The size and shape of things are presented to us by our senses, yet every one knows that size and shape are not sensations.”[4]

The argument restated: Berkeley's doctrine that the senses provide only sensations to the mind is said to be a mistaken doctrine because everyone knows the size and shape of things are not sensations.

What everyone is said to “know” in this case is what everyone is assumed to believe, and this is not relevant for the proof of Berkeley's doctrine. So the fallacy of ad populum occurs.

(And, as well, from a philosophical point of view, the fallacy of petitio principii occurs in that the argument presupposes the distinction between primary and secondary qualities, which Berkeley did not distinguish since he regarded both kinds of qualities as mind-dependent.) - “Invisible Women: Data Bias in a World Designed for Men, by Caroline Criado Perez. This is not the type of book I would usually read — it's common knowledge, at least to very petite women who shop for the latest fashions in the children's section, that it's a world designed for guys. But oh boy, there's so much more to it.”[5]An ad populum (bandwagon) fallacy is used here for the foundation of a converse accident fallacy. On the basis of petite women's common belief that shopping for children's clothes is difficult, the author concludes the world is biased for men. Even for a facetious argument, logic sense is lacking.

- “The Trump administration is being sued over its plans to include a question about citizenship in the 2020 Census, which California Attorney General Xavier Becerra (D) says ‘is not just a bad idea — it is illegal.’ No, it's not. There is nothing wrong with asking about citizenship. Canada asks a citizenship question on its census. So do Australia and many other U.S. allies.[6]The argument is since many U.S. allies have a census-citizenship question; therefore, it is legal for the U.S. to have a census-citizenship question also. The fact that other countries have such a question is irrelevant to the legality of the question in the U.S. The fallacy of ad populum occurs, and this irrelevancy is also an ignoratio_elenchi_ diversion from the issue of whether or not a citizenship-question conforms to U.S. law.

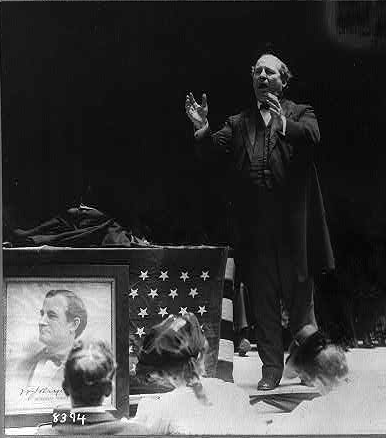

- “Having behind us the producing masses of this nation and the world, supported by the commercial interests, the laboring interests and the toilers everywhere, we will answer their demand for a gold standard by saying to them: You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns, you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.”[7]William Jennings Bryan's argument:

Establishment of the gold standard will hurt workers

The passage is a classic example of an ad populum rhetorical fallacy on account of its intense emotive significance. The effectiveness of the argument depends upon the truth of the premise.

∴ The gold standard should not be adopted. - “Some of you hold to the doctrine of States' Rights as applying to woman suffrage. Adherence to that theory will keep the United States far behind all other democratic nations upon this question. A theory which prevents a nation from keeping up with the trend of world progress cannot be justified.” [italics original][8]Ad populum_ (bandwagon) fallacy occurs. From the trend of “world progress,” the author concludes that supporting the doctrine of states rights would prevent the U.S. from keeping with with the progress of other nations with respect women's suffrage. The question of suffrage in the U.S. should be determined by what is right rather than by whether or not other countries deny or approve of suffrage.

- “[T]he human soul is immortal, because all learned men agree that anything which does not come out of the potentiality of matter is incorruptible and immortal.”[9]The ad populum fallacy occurs since the generalization, even if true, that all learned men would agree that the soul does not arise from matter, this agreement is not a proof that the human soul is mortal. The common belief assumed here is not common knowledge.

- “[W]hen Alexander was in Asia, the Chaldeans reckoned 473,000 years, since they first observed the stars; not that so long a space was understood by themselves of years … [f]or it is probable, that these years were but periods of cycles of short length … These reports of the early efforts of the Chaldeans, are corroborated by the testimony of many eastern writers.”[10]No fallacy is committed. The argument presented is since many Eastern writers corroborated the reports of the Chaldean knowledge of astronomy for some years, it is probable that the Chaldeans had such knowledge. How many years since they first observed the stars is not at issue.This ABC-TV 1992 advertisement is quoted in a popular logic textbook:

“Why are so many people attracted to the Pontiac Grand Prix? It could be that so many people are attracted to the Grand Prix!”[11]

(This passage has been presented in all versions of this textbook as a “recent” ad populum example for the past forty years. The Pontiac Grand Prix stopped production in 2008.)The logic textbook cites this advertisement as committing the ad populum fallacy. Undoubtedly, the authors are possibly assuming that there is an implied elliptical conclusion, translated something like this:Many people are attracted to the Pontiac Grand Prix.

or

∴ [The Pontiac Grand Prix is an excellent automobile.]

Many people are attracted to the Pontiac Grand Prix.

But this interpretation is unlikely since the original passage, as it is presented is this argument:

∴ [You should also be attracted to the Pontiac Grand Prix.]Many people are attracted to the Pontiac Grand Prix

This argument commits the fallacy of petitio principii (circular argument), assuming the point at issue.

∴ Many people are attracted to the Pontiac Grand Prix.

“I am one black woman who believes in America and loves this country, who believes that our future lies in Christianity, capitalism and the Constitution. And I am here to tell you that tens of millions of American of all backgrounds are with me — and are with President Trump. Let's stand up and fight, fight those that hate our nation and what it stands for. Let's win back our nation, our freedom and our God for our future, for our children. God Bless America.” [12]The emotive ad populum rhetorical fallacy occurs, turning on the attempt to garner support for President Trump and his policies by touting an American appeal to inflated popular patriotic attitudes of the Republican party.“We all believe such preachers as Mr. Raskin. He is so nearly right, his ideals are so very high, that most people assent — while they have no difficulty in evading them and going on their way as if a breath of wind had fanned their faces, and no voice of truth had stirred their spirits.”[13]No fallacy is present in this passage. Implicitly, the argument can be translated as:Mr. Raskin is so nearly right.

The premises provide some relevant evidence for the truth of the conclusion.

His ideals are very high

∴ We believe him.“[I]nternational inspectors would monitor Iran's facilities, and if Iran is caught breaking the agreement economic sanctions would be imposed again. … Snapback sanctions? Everyone knows that once the international sanctions are lifted, they are never coming back.”[14]The standard ad populum (bandwagon) fallacy is presented. Mr. Krauthammer might be correct that most people believe that if the sanctions are lifted, they will never come back, but reasons are not provided for his conclusion that this is something that is known to be true.“[John Dickie] is an industrious outsider wholly reliant on published literature [of] deeply flawed documents … Dickie's contemptuous dismissal of the contention that annexation was economically disastrous for Sicily contradicts the consensus of economic historians who have published on the subject.”[15]Not an ad poplum fallacy since the authorities cited as writers who are economic historians of the subject in question are relevant authorities in their field.

1. Martha Angle and Robert Walters, “In Washington: The Public Isn't Buying” Bowling Green Daily News 123 No. 212 (September 6, 1977), 16.↩

2. Erich Przywara, An Augustine Synthesis (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1958), 122.↩

3. Abraham Lincoln, et al. The Writings of Abraham Lincoln: 1858-1861 vol. 5 (New York: The Lamb Publishing Company, 1906), 261.↩

4. Thomas Collins Simon, On the Nature and Elements of the External World, or, Universal Immaterialism Fully Explained and Newly Demonstrated (London: J. Churchill, 1847), 183. In point of fact, Reid appealed to common sense rather than to what “everyone knows.” Thomas Reid, An Inquiry into the Human Mind, On the Principles of Common Sense, 3rd ed. (London: T. Cadell, 1769), 381.↩

5. Esther Cepeda, “Get Ready to Learn from These Books, Because Ignorance Is Not Bliss,” Index-Journal 101 no. 277 (December 20, 2019), 8A. Also available here under this title: “Must-Read (But Depressing) Books with a Social Justice Bent.”↩

6. Cal Thomas, “Extortionist in Chief,” Index-Journal 94 no. 297 (February 23, 2013), 9A. ↩

7. William Jennings Bryan, “In the Chicago Convention,” Speeches of William Jennings Bryan (New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company, 1913), I-249. (Bryan's “The Cross of Gold Speech”)↩

8. Carrie Chapman Catt, “An Address to the Congress of the United States,” Handbook of the National American Woman Suffrage Association 49th Annual Convention (National Woman Suffrage Publishing, 1917), 67. ↩

9. Donato Acciaiuoli, “Commentary on the Nichomachean Ethics” ed. Jill Kraye in Cambridge Translations of Renaissance Philosophical Texts vol. I, Moral Philosophy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 55.↩

10. John W. Draper, “Remarks of the Idolatry and Philosophy of the Zabians,” The American Journal of Science and Arts Vol. 28 (July, 1835), 203.↩

11. Irving M. Copi, Carl Cohen, and Victor Rodych, Introduction to Logic 15th ed. (New York: Routledge, 2018), 103.↩

12. Star Parker, “Response to the State of the Union,” Index-Journal 100 no. 328 (February 9, 2019), 9A.↩

13. Richard Pardow, “The Bagman's Little Story,” The Central Literary Magazine 13 no. 1 (1897-1898), 70.↩

14. Charles Krauthammer, “Just Who Is Helping Iran's Hard-Liners?” Index Journal 97 No. 64 (August 10, 2015), 6A.↩

15. Edward Luttwak, “ Honoured Society,” in “Letters,” London Review of Books 35 no. 21 (Novenber 7, 2013), 4.↩

Send corrections or suggestions to

larchie[at]philosophy.lander.edu

Read the disclaimer

concerning this page.

1997-2020 Licensed under GFDL and

Creative

Commons 3.0

The “Copyleft” copyright assures the user the freedom

to use, copy, redistribute, make modifications with the same terms.

Works for sale must link to a free copy.

The “Creative Commons” copyright assures the user the freedom

to copy, distribute, display, and modify on the same terms. Works for sale

must link to a free copy.

Arguments | Language | Fallacies | Propositions | Syllogisms | Translation | Symbolic

![]()

![]()