|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Homepage » Logic » Argument Topics Index » Square of Opposition |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

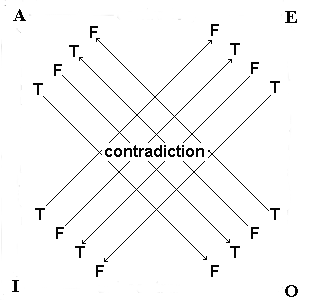

![-The Square of Opposition- [woodcut by S.J. Swinbourne], _Picture_Logic_(London: Longmans, Green, 1875), 104. -The Square of Opposition- [woodcut by S.J. Swinbourne], _Picture_Logic_(London: Longmans, Green, 1875), 104.](images/graphics/sq_opp515x524.png)

The Traditional

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I. If you are unfamiliar with the important terms

introduced previously: name, form, quantity, quality and distribution,

then be sure to review them before studying the square of opposition.

|

||||

| II. The Traditional Square of

Opposition |

||||

| A. Logical opposition occurs among standard form categorical propositions if ... | ||||

| 1. they have the same subject and predicate terms and... | ||||

| 2. they differ in quality or

quantity or both. |

||||

| B. Consider the possible ways

opposition between categorical statements can arise in terms of their

differing quantity and quality. There are four possibilities: |

||||

| Case 1: the statements could differ in both their the quantity and quality. | ||||

| Case 2: the statements could differ the quality, but not the quantity. | ||||

| Case 3: they could differ in quantity, but not the quality. | ||||

| Case 4: they could have

the same quantity and quality. (Of course, this case is trivial since two statements with the same subject and predicate terms and having the same quality and quantity are the same logicallly identical statement.) |

||||

| III. Case 1: The

propositions have different quantity and quality. |

||||

A. Suppose we have an A

proposition:

“All philosophers are idlers.” |

||||

| 1. What proposition is the

denial of this statement? That is, what proposition differs in both quantity and quality? Answer: The particular negative, or the O proposition differs in both quantity and quality: “Some philosophers are not idlers.” |

||||

|

2. Consider the logical “geography” of these two statements,

the A and the O statements, as pictured on the right side

of this page. The left-hand circle represents the class of philosophers. The right-hand circle represents the class of idlers. The “X” represents ”some” individual (i.e, at least one individual” exists where it is placed). The shading represents no individual exists in the area it is placed). Note how the diagrams exhibit contradictory contradictory information. In the A diagram, “All philosophers are idlers,” the shading indicates no individual is present in the left-hand lune; In the O diagram, the “X” indicates the opposite: at least one individual is present in the left-hand lune. If we superimpose the A diagram on top of the O diagram, we obtain the diagram shown by clicking on this “Venn Diagram” button: |

|

|||

|

||||

3. This type of opposition is called contradiction and is defined

as follows:

Two propositions are contradictories if they cannot both be true and they cannot both be false.In other words, the statements have opposite truth values. |

||||

B. Suppose we now start with

an E proposition:

“No philosophers are idlers.”; |

||||

| 1. What proposition is the

denial of the E statement? I.e., what proposition differs in both quantity and quality of “ No philosophers are idlers”? Answer:The particular affirmative or an I proposition is so opposed: “Some philosophers are idlers.” |

||||

2. Notice what would happen if both of these statements were

claimed to be true at the same time:

The diagram would both both shading and an X in the lens area where the circles overlap.This state of affairs is, of course, logically impossible, and is shown by clicking on the “Venn Diagram” button: |

|

|||

|

||||

|

4. This opposition between the A and O statement is also

called contradiction: they cannot both be true and they cannot

both be false. Note that there is a kind of symmetry to the logical relation of contradiction. Hence, we do not have to examine the I and O propositions separately in order to find their contradictories since they were discovered by investigating the A and O statements.  |

||||

| 5. These results can be summarized

on the complete diagram of the Square of

Opposition toward which we will complete in this page's presentation.

|

||||

| IV. Case 2: (first part) the propositions differ in quality but are the same in quantity. | ||||

| A. Suppose we start again with an A

proposition: "All philosophers are idlers." What proposition is the same quantity but differs in quality? |

||||

| B. The universal negative or the E

proposition does so: "No philosophers are idlers." |

||||

| C. This kind of opposition is called contrariety. A and E are contraries. | ||||

| D. Two propositions are said to be contraries if they cannot both be true, although they might both be false. | ||||

| If both the A and the E could be true at the same time, then the subject class would be empty. In the traditional square, we assume that the subject of the proposition refers to something that exists. |  |

|||

|

||||

| Case 2 (second part): Suppose, on the

other hand, we start with an I proposition: "Some philosophers are idlers." What proposition is the same in quantity, but differs in quality? |

||||

| A. The particular negative or the O

proposition does so: "Some philosophers are not idlers." |

||||

| B. This logical relation is called subcontrariety. Two propositions are said to be subcontraries if they cannot both be false, although they might both be true. In other words, I and O are subcontraries of each other. | ||||

| What would happen if both the I

and O statements could be false? The diagram shows that if

they were then the subject class would have to be the empty class! |

E is a false I E is a false I |

|||

A is a false O A is a false O |

||||

| C. We can now summarize our results before moving to Case 3. I and O can both be true but they need not be. The only thing known is that they cannot both be false. |  |

|||

|

||||

| V. Case 3 (part 1): The propositions agree in quality but differ in quantity. | ||||

| A. Again, let us start with the A

proposition: "All philosophers are idlers." What proposition is the same in quality but differs in quantity? |

||||

| 1. The particular affirmative or the I

proposition does so: "Some philosophers are idlers." |

||||

| 2. If the A statement is true, we know that the I statement has to be true, (unless there are no members of the subject class, i.e., it's an empty subject class). | ||||

| 3. Note carefully the following truth relations for this logical relation called subalternation: | ||||

| If A is true, then I is true. (Otherwise, the subject class is empty.) | ||||

| If A is false, then I is undetermined in truth value. | ||||

| If I is true, then A is undetermined in truth value. | ||||

| If I is false, then A is false. (Otherwise, the subject class is empty.) | ||||

| B. These are summarized on the Square of Opposition. | ||||

| Case 3 (part two): our last analysis. Let

us look at the E proposition: "No philosophers are idlers." |

||||

| A. What proposition is the same in quality but

differs in quantity from the E? The O statement does so since it is

particular and negative. "Some philosophers are not idlers." |

||||

| B. A quick look at the Venn Diagrams yields the following truth values listed below. |  |

|||

|

||||

| If E is true, then O is true. (Otherwise the subject class is empty.) | ||||

| If E is false, then O is undetermined in truth value. | ||||

| If O is true, then E is undetermined in truth value. | ||||

| If O is false, then E is false. (Otherwise, the subject class would be empty.) | ||||

| C. In sum, then E and O

are related by subalternation. The logical relation described above

is called subalternation. E is often termed the “superaltern” of O, the “subaltern.” |

||||

|

For convenience all four logical relations on the Square of Opposition

are sketched out on the summary chart on this page:

Summary of the Square of OppositionAlso be sure to try the practice quiz on this page: Exercise on the Square of Opposition. |

||||

Read the disclaimer concerning this page.

1997-2020 Licensed under GFDL and Creative Commons 3.0

The “Copyleft” copyright assures the user the freedom to

use, copy, redistribute, and make modifications with the same

terms. Works for sale must link to a free copy.

The “Creative Commons” copyright assures the user the

freedom to copy, distribute, display, and modify on the same

terms. Works for sale must link to a free copy.

Arguments | Language | Fallacies | Propositions | Syllogisms | Translation | Symbolic

![]()

![]()