The Reading Selection from Ethical Studies

[Morality Is Not a Means]

Why should I be moral? The question is natural, and yet seems strange. It appears to be one we ought to ask, and yet we feel, when we ask it, that we are wholly removed from the moral point of view.

To ask the question Why? is rational; for reason teaches us to do nothing blindly, nothing without end or aim. She teaches us that what is good must be good for something, and that what is good for nothing is not good at all. And so we take it as certain that there is an end on one side, means on the other; and that only if the end is good, and the means conduce to it, have we a right to say the means are good. It is rational, then, always to inquire, Why should I do it?

But here the question seems strange. For morality (and she too is reason) teaches us that, if we look on her only as good for something else, we never in that case have seen her at all. She says that she is an end to be desired for her own sake, and not as a means to something beyond. Degrade her, and she disappears; and, to keep her, we must love and not merely use her. And so at the question Why? we are in trouble, for that does assume, and does take for granted, that virtue in this sense is unreal, and what we believe is false. Both virtue and the asking Why? seem rational, and yet incompatible one with the other; and the better course will be, not forthwith to reject virtue in favour of the question, but rather to inquire concerning the nature of the Why?

Why should I be virtuous? Why should I? Could anything be more modest? Could anything be less assuming? It is not a dogma; it is only a question. And yet a question may contain (perhaps must contain) an assumption more or less hidden; or, in other words, a dogma. Let us see what is assumed in the asking of our question.

In ‘Why should I be moral?’ the ‘Why should I?’ was another way of saying, What good is virtue? or rather, For what is it good? and we saw that in asking, Is virtue good as a means, and how so? we do assume that virtue is not good, except as a means. The dogma at the root of the question is hence clearly either (1) the general statement that only means are good, or (2) the particular assertion of this in the case of virtue.

To explain; the question For what? Whereto? is either universally applicable, or not so. It holds everywhere, or we mean it to hold only here. Let us suppose, in the first place, that it is meant to hold everywhere.

Then (1) we are taking for granted that nothing is good in itself; that only the means to something else are good; that ‘good’ in a word, =‘good for’, and good for something else. Such is the general canon by which virtue would have to be measured.

No one perhaps would explicitly put forward such a canon, and yet it may not be waste of time to examine it.

[Could Good Only Be a Means?]

The good is a means: a means is a means to something else, and this is an end. Is the end good? No; if we hold to our general canon, it is not good as an end: the good was always good for something else, and was a means. To be good, the end must be a means, and so on for ever in a process which has no limit. If we ask now What is good? we must answer, There is nothing which is not good, for there is nothing which may not be regarded as conducing to something outside itself. Everything is relative to something else. And the essence of the good is to exist by virtue of something else and something else for ever. Everything is something else, is the result which at last we are brought to, if we insist on pressing our canon as universally applicable. …

It is quite true that to ask Why should I be moral? is ipso facto to take one view of morality, is to assume that virtue is a means to something not itself. But it is a mistake to suppose that the general asking of Why? affords any presumption in favour of, or against, any one theory. If any theory could stand upon the What for? as a rational formula, which must always hold good and be satisfied, then, to that extent, no doubt it would have an advantage. But we have seen that all doctrines alike must reject the What for? and agree in this rejection, if they agree in nothing else; since they all must have an end which is not a mere means. And if so, is it not foolish to suppose that its giving a reason for virtue is any argument in favour of Hedonism, when for its own end it can give no reason at all? Is it not clear that, if you have any Ethics, you must have an end which is above the Why? in the sense of What for?; and that, if this is so, the question is now, as it was two thousand years ago, Granted that there is an end, what is this end? …

[Virtue is an End-in-Itself]

[W]hat is clear at first sight is, that to take virtue as a mere means to an ulterior end is in direct antagonism to the voice of the moral consciousness.

That consciousness, when unwarped by selfishness and not blinded by sophistry, is convinced that to ask for the Why? is simple immorality; to do good for its own sake is virtue, to do it for some ulterior end or object, not itself good, is never virtue; and never to act but for the sake of an end, other than doing well and right, is the mark of vice. And the theory which sees in virtue, as in money-getting, a means which is mistaken for an end, contradicts the voice which proclaims that virtue not only does seem to be, but is, an end in itself.

Taking our stand then, as we hope, on this common consciousness, what answer can we give when the question Why should I be moral?, in the sense of What will it advantage me?, is put to us? Here we shall do well, I think, to avoid all praises of the pleasantness of virtue. We may believe that it transcends all possible delights of vice, but it would be well to remember that we desert a moral point of view, that we degrade and prostitute virtue, when to those who do not love her for herself we bring ourselves to recommend her for the sake of her pleasures. Against the base mechanical βανανδια[1] which meets us on all sides, with its ‘what is the use’ of goodness, or beauty, or truth, there is but one fitting answer from the friends of science, or art, or religion and virtue, ‘We do not know, and we do not care.’ …

What more are we to say? If a man asserts total scepticism, you cannot argue with him. You can show that he contradicts himself; but if he says, "I do not care" there is an end of it. So, too, if a man says, "I shall do what I like, because I happen to like it; and as for ends, I recognize none" you may indeed show him that his conduct is in fact otherwise; and if he will assert anything as an end, if he will but say, "I have no end but myself", then you may argue with him, and try to prove that he is making a mistake as to the nature of the end he alleges. But if he says, "I care not whether I am moral or rational, nor how much I contradict myself", then argument ceases. We, who have the power, believe that what is rational (if it is not yet) at least is to be real, and decline to recognize anything else. For standing on reason we can give, of course, no further reason; but we push our reason against what seems to oppose it, and soon force all to see that moral obligations do not vanish where they cease to be felt or are denied.

Has the question, Why should I be moral? no sense then, and is no positive answer possible? No, the question has no sense at all; it is simply unmeaning, unless it is equivalent to, Is morality an end in itself; and, if so, how and in what way is it an end? …

What remains is to point out the most general expression for the end in itself, the ultimate practical 'why'; and that we find in the word self-realization … All that we can do is partially to explain it, and try to render it plausible.

But passing by [that] which we can not here expound and which we lay no stress on, we think that the reader will probably go with use so far as this, that in desire what we want, so far as we want it, is ourselves in some form, or is some state of ourselves; and that our wanting anything else would be psychologically inexplicable. …

If we may presuppose in the reader a belief in the doctrine that what is wanted is a state of self, we wish, standing upon that, to urge further that the whole self is present in its states, and that therefore the whole self is the object aimed at; and this is what we mean by self-realization. …And must we not say that to realize self is always to realize a whole, and that the question in morals is to find the true whole, realizing which will practically realize the true self. …

[Why I Am to be Moral?]

We have attempted to show (1) That the formula of ‘what for?’ must be rejected by every ethical doctrine as not universally valid; and the hence no one theory can gain the smallest advantage (except over the foolish) by putting it forward: that now for us (as it was for Hellas[2] the main question is: There being some end, what is that end? And (2), with which second part, if it fall, the first need not fall, we have endeavoured briefly to point out that the final end, with which morality is identified, or under which it is included, can be expressed not otherwise than by self-realization.

To conclude—If I am asked why I am to be moral, I can say no more than this, that what I can not doubt is my own being now, and that, since in that being is involved a self, which is to be here and now, and yet in this here and now is not, I therefore can not doubt that there is an end which I am to make real; and morality, if not equivalent to, is at all events included in this making real of myself.

If it is absurd to ask for the further reason of my knowing and willing my own existence, then it is equally absurd to ask for the further reason of what is involved therein. The only rational question here is not Why? but What? What is the self that I know and will? What is its true nature, and what is implied therein? What is the self that I am to make actual, and how is the principle present, living, and incarnate in its particular modes of realization?

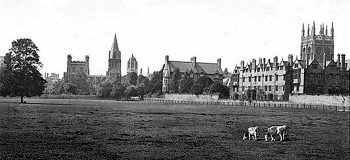

Merton and Christ Church College, Oxford, England Bradley was elected as a Fellow to Merton College, terminable on marriage. (Adapted from Library of Congress)