|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

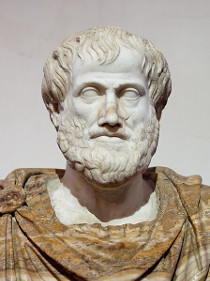

Ethics Homepage > Self-Interest > Aristotle |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Philosophy 302: Ethics |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I. With respect to the good, right, and happiness,

the good for Aristotle is not a disposition to act in a certain way.

The good involves a teleological system where living well and doing

well are the highest end of life: goods such as strength, wealth, and

friendships facilitate a well-lived life. |

|||||||||||||

|

|

A. For Aristotle the (highest) good is that to which

all things aim. Something is good if it performs its proper function.

E.g., a good coffee cup is good if it is made of good materials,

is of the right size and shape, retains heat, and is convenient in use,

and so forth. A good red oak tree is well shaped, is healthy, has good

soil and light, and so on.

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

1. A right action is that which is conducive to the good, and different goods correspond to the differing sciences and arts. |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

2. "The good" or best good is that which

is desired for its own sake and for the sake which we desire all other

ends or goods. E.g. we desire friends not as something good in

itself but as something to help facilitate eudaemonia. |

|||||||||||

|

|

B. The good of human beings cannot be answered

with the exactitude of a mathematical problem since mathematics

starts with general principles and argues to conclusions.

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

1. Ethics starts with our actual moral judgments prior to our ability to formulate of general principles. |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

2. Aristotle presupposes people have a natural tendency

to seek what they think is good or beneficial. |

|||||||||||

|

|

C. Aristotle distinguishes between happiness

(eudaemonia) and moral virtue: |

||||||||||||

|

|

|

1. Moral virtue is not the end of life, for some morally virtuous persons are inactive, miserable and unhappy. |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

2. Happiness, the end of life and that to which all

persons aim, is activity in accordance with reason. |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

a. Happiness is an activity involving both moral and intellectual arete. |

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

b. Some external goods, such as friendship,

sufficient wealth, and sufficient influence, are necessary in

order to exercise that activity. |

||||||||||

|

II. The Good Character. |

|||||||||||||

|

|

A. People have a natural capacity for good

character, and it is developed through practice. The capacity

does not come first — it's developed through practice.

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

| 1. The sequence of character development in human behavior raises the question of which is preeminent — acts or dispositions. Their interaction is elucidated by Aristotle's distinction between acts which create good dispositions and acts which flow from the good disposition once good character has been created. | |||||||||||||

| 2. Arete is a disposition developed out of a capacity by the proper exercise of that capacity. | |||||||||||||

|

|

|

3. Habits are developed through acting; a person's

character is the structure of habits formed by what we do.

|

|||||||||||

|

|

B. Virtue, arete, or excellence is defined

as a mean between two extremes of excess and defect with respect to a

feeling or action as the practically wise person would determine it.

This mean cannot be calculated a priori. |

||||||||||||

|

|

|

1. The mean is relative to the individual and

the individual's circumstances. For example, consider the following

traits: |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

Defect |

Mean |

Excess |

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

cowardliness |

courage |

rashness |

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

humility |

pride |

vanity |

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

frugal |

giving |

liberal |

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

2. The level of courage necessary is different for a philosophy student, a commando, and a systems programmer. |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

3. Phronesis or practical wisdom is the ability to see the right thing to do in the circumstances. Notice, especially here, Aristotle's theory does not imply ethical relativism because of the appropriate standards human action in accordance with the appropriate mean for that person in that situation. |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

4. In the ontological

dimension of virtue as a factual instance, virtue is a mean; in the axiological

dimension of virtue as a value, it is an extreme or an excellence.

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

5.Some presumptively virtuous behaviors can be an

extreme as when, for example, the medieval philosopher Peter

Abélard explains:

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

6. Hartmann's Diagram:  The diagram illustrates virtue considered in its ontological dimension

as a mean and virtue in the axiological dimension as an extreme or

an excellence. [Nicolai Hartmann, Ethik

(Berlin: W. de Gruyter, 1926), 401.]

The diagram illustrates virtue considered in its ontological dimension

as a mean and virtue in the axiological dimension as an extreme or

an excellence. [Nicolai Hartmann, Ethik

(Berlin: W. de Gruyter, 1926), 401.] |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

7. Pleasure and pain are powerful determinants of

our actions. |

|||||||||||

|

III. Pleasure is the natural accompaniment of unimpeded activity. Pleasure, as such, is neither good nor bad. |

|||||||||||||

|

|

A. Even so, pleasure is something positive when its effect is to perfect the exercise of activity. Everything from playing chess to making love is improved with skill. |

||||||||||||

|

|

B. Pleasure cannot be directly sought — it is the side-product of activity. Pleasure is only one element in the development of happiness. |

||||||||||||

|

|

C. The good person, the one who has attained

eudaemonia, is the standard by which pleasant or unpleasant

is known. (For more on Aristotle's view of pleasure, see Aristotle on Pleasure on this website.)

|

||||||||||||

|

IV. Friendship: a person's relationship to a friend is the same as the relation to oneself, according to Aristotle. A good friend is thought of as a second self. |

|||||||||||||

|

|

A. In friendship a person loves himself not as someone seeking wealth for himself, but as someone who gives his money away to receive honor. |

||||||||||||

|

|

B. Aristotle distinguishes three kinds of friendship: |

||||||||||||

|

|

|

1. Utility: friendships of worthwhile mutual benefit in accomplishment |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

2. Pleasure: friendships of contentment, gratification, and mutual while having a good time together. |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

3. The Good: friendships of virtue and character who

flourish together — a friendship which endures as long as both retain

their character. |

|||||||||||

|

V. The Contemplative Faculty — the exercise of perfect happiness in intellectual or philosophic activity. |

|||||||||||||

|

|

A. Reason is the highest faculty of human beings. We can engage in it longer than other activities. |

||||||||||||

|

|

B. Contemplation is the highest part of our self and form of activity. Philosophy is loved as an end-in-itself, and consequently Aristotle implies the realization of eudaemonia (or happiness) requires leisure and self-sufficiency as an environment for contemplation. |

||||||||||||

Recommended Sources

Quiz

on Aristotle's Ethics: Aristotle's ethical theory reviewed in

true/false questions.

Quiz

on the Doctrine of the Mean: A short quiz on Aristotle's Doctrine of

the Mean from Introduction to Philosophy.

Aristotle's

Ethics: An excellent discussion from the Stanford

Encyclopedia of Philosophy of Aristotle's ethics drawn from the Nicomachean

Ethics and the Eudemian Ethics by Richard Kraut.

Send corrections or suggestions to

webmaster@philosophy.lander.edu |

![]()

![]()