Main Divisions of Philosophy

It may well be wondered, at this point, as to the exact difference between philosophy and the sciences.[1] The following excerpt from the entry "Philosophy" in the authoritative 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica explains one aspect of this relation well and is well worth reading carefully:

In distinguishing philosophy from the sciences, it may not be amiss at the outset to guard against the possible misunderstanding that philosophy is concerned with a subject-matter different from, and in some obscure way transcending, the subject-matter of the sciences. Now that psychology, or the observational and experimental study of mind, may be said to have been definitively included among the positive sciences, there is not even the apparent ground which once existed for such an idea. Philosophy, even under its most discredited name of metaphysics, has no other subject-matter than the nature of the real world, as that world lies around us in everyday life, and lies open to observers on every side. But if this is so, it may be asked what function can remain for philosophy when every portion of the field is already lotted out and enclosed by specialists?

Philosophy claims to be the science of the whole; but, if we get the knowledge of the parts from the different sciences, what is there left for philosophy to tell us? To this it is sufficient to answer generally that the synthesis of the parts is something more than that detailed knowledge of the parts in separation which is gained by the man of science. It is with the ultimate synthesis that philosophy concerns itself; it has to show that the subject-matter which we are all dealing with in detail really is a whole, consisting of articulated members. Evidently, therefore, the relation existing between and the sciences will be, to some extent, one of reciprocal influence.

Newton's Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematics, title page, pages 354-355, State Library of Victoria

The author of this entry is pointing to the unifying and systematizing methods of philosophy for other disciplines. The coherence of the whole is made possible by consistent fundamental principles. The article continues:

The sciences may be said to furnish philosophy with its matter, but philosophical criticism reacts upon the matter thus furnished, and transforms it. Such transformation is inevitable, for the parts only exist and can only be fully, i.e. truly, known in their relation to the whole. A pure specialist, if such a being were possible, would be merely an instrument whose results had to be co-ordinated and used by others. Now, though a pure specialist may be an abstraction of the mind, the tendency of specialists in any department naturally is to lose sight of the whole in attention to the particular categories or modes of nature's working which happen to be exemplified, and fruitfully applied, in their own sphere of investigation; and in proportion as this is the case it becomes necessary for their theories to be co-ordinated with the results of other inquirers, and set, as it were, in the light of the whole.

This task of co-ordination, in the broadest sense, is undertaken by philosophy; for the philosopher is essentially what Plato, in a happy moment, styled him, &sgr;&ugr;&ngr;&ogr;&pgr;&tgr;&igr;&kgr;&oacgr;&sgr;, the man who takes a "synoptic" or comprehensive view of the universe as a whole. The aim of philosophy (whether fully attainable or not) is to exhibit the universe as a rational system in the harmony of all its parts; and accordingly the philosopher refuses to consider the parts out of their relation to the whole whose parts they are. Philosophy corrects in this way the abstractions which are inevitably made by the scientific specialist, and may claim, therefore, to be the only "concrete" science, that is to say, the only science which takes account of all the elements in the problem, and the only science whose results can claim to be true in more than a provisional sense.[2]

The foundational and unifying aspects of philosophy form the characteristics of our beginning study of philosophical inquiry in this introductory set of readings. It is important to point out however that these characteristics are not " the be-all and end-all" of philosophy.

Epistemology: the Study of Knowledge

Traditionally philosophical questions have been grouped into three areas which we will very briefly describe and suggest a few examples. Given the nature of philosophical inquiry, these areas are interdependent. Undoubtedly, it will occur to you that each example provided provided below has characteristics related to other areas of philosophy, and, indeed, philosophical problems are rarely limited to just one area of the discipline.

(1) Epistemology (theory of knowledge): the inquiry into what knowledge is, what can be known, and what lies beyond our understanding; the investigation into the origin, structure, methods, and validity of justification and knowledge; the study of the interrelation of reason, truth, and experience.

As an example of an epistemological problem, consider the lottery paradox, an argument occasionally used to support skepticism: the doctrine that genuine knowledge is impossible. Some persons believe nothing in this life can be certain, anything is possible, and nothing is "for sure."[3] Even if we do not accept radical skepticism, supposedly, the best that we can do as human beings is to justify our beliefs in terms of their probability. On this view, we could be justified in believing somethings true if it is highly probable, but we would not be justified in believing something if it has a very low probability of being true. Admittedly, this kind of justification is not certainty or knowledge. Let's examine these assumptions more carefully.

Suppose we. with thousands of other persons, enter a fair-ticket lottery. Since the probability of our winning the lottery is quite low, on the above assumption, we would be fully justified in believing that we will not win.

What's more, since all ticket-holders have the same chance as we do to win, on the same assumption, we would be fully justified in believing that each one of those individuals will not win either. Thus, we are justified in concluding that no ticket will win since the probability of any one ticket winning is quite low. [4]

Of course, at the same time we know that this "reasonable" belief is mistaken because we know that in a fair lottery one ticket will win. The "lottery paradox" indicates beyond doubt that knowledge cannot result directly from empirical inquiry, since any belief could only involve probable conclusions—conclusions which are fallible.

Another perplexing example from epistemology is Bertrand Russell's Five-Minute World Hypothesis: suppose the universe were suddenly created five minutes ago, complete with memories, historical and geological records, and so forth. That is, at the moment of creation, the universe would have all the evidence that it was billions of years old already "packed in." How could it ever be known that the creation of the universe did not occur five minutes ago?

The hypothesis initially seems implausible, yet how can we know that the universe wasn't created a few minutes ago? Certainly the Five-Minute World hypothesis is inconsistent with many of our other beliefs. If it were true, we would have to give up these other beliefs if we were to hold it, but how could we prove beyond any shadow of doubt what is the case? From a purely empirical point of view, no evidence is available which could prove that God isn't constantly creating the universe moment by moment. In fact, as we will see in Part III of this text, some persons who believe in predestination eschew the notion of causality and believe God actually does create the universe moment by moment.

Many times in philosophy, proposed solutions to specifically formulated problems such as these lead to amazing shifts in perspective by which the nature of the universe can be comprehended.

Metaphysics (Ontology): the Study of Reality

(2) Metaphysics or Ontology (theory of reality): the inquiry into what is real as opposed to what is appearance, either conceived as that which the methods of science presuppose, or that with which the methods of science are concerned; the inquiry into the first principles of nature; the study of the most fundamental generalizations as to what exists.

A typical example of an ontological problem is the well-known difficulty of finding "a criterion of individuation" for distinguishing things. Suppose we are asked to sort potatoes into two baskets—one for the large ones and one for small ones. For the most part, we wouldn't expect many problems with such a straightforward task.

Very large potatoes would be placed in the basket selected for the large potatoes, and tiny potatoes would be placed in the basket selected for the small potatoes. But, of course, there is a problem. What shall we do about the potatoes which are difficult to judge—for example, a potato sized somewhere between the large and small ones: e.g., one that is short and wide, one that is long and thin, or one that is just plain "medium-sized"?

We could set up a criterion of "potato-ness" by means of a precising or an operational definition which clearly distinguishes between "large" and "small"—perhaps by measuring volume, weight, or length in order to mark accurately the difference. But then would such a criterion thereby entail that a medium potato does not exist?

If we admit existence of medium potatoes, then our "criterion of potato-ness" must be revised to take account of the "newly discovered entity" of the medium potato. However, as you may have already guessed, our problems have now doubled. We now need criteria to distinguish the large from the medium and the medium from the small. Ontologically, a new problem arises. Should we admit the existence of medium-large and medium-small potatoes? If so, lamentably, our problem again propagates itself again in the same manner.

Do you think that the kinds of things that exist in the universe are independent of the concepts we use to describe them? Or do our concepts determine the kinds of things we can know to exist? Do the mere actions of perceiving and thinking limit the content of our ideas? What could be the reality beyond our ideas?

Axiology: the Study of Value

(3) Axiology (theory of value): the inquiry into the nature, criteria, and metaphysical status of value. Axiology, in turn, is divided into two main parts: ethics and æsthetics.

Although the term "axiology" is not widely used outside of philosophy, the problems of axiology include (1) how values are experienced, (2) the kinds of value, (3) the standards of value, and (4) in what sense values can be said to exist. Axiology, then is the subject area which tries to answer problems like these:

How are values related to interest, desire, will, experience, and means-to-end?

How do different kinds of value interrelate?

Can the distinction between intrinsic and instrumental values be maintained?

Are values ultimately rationally or objectively based?

What is the difference between a matter of fact and a matter of value?

There are two main subdivisions of axiology: ethics and æsthetics. Ethics involves the theoretical study of the moral valuation of human action—it's not just concerned with the study of principles of conduct. Æsthetics involves the conceptual problems associated with the describing the relationships among our feelings and senses with respect to the experience of art and nature. Each of these subdivisions are briefly characterized below.

(a) Æsthetics: the inquiry into feelings, judgments, or standards concerning the nature of beauty and related concepts such as the tragic, the sublime, or the moving—especially in the arts; the analysis of the values of sensory experience and the associated feelings or attitudes in art and nature; the theories developed in les beaux arts.

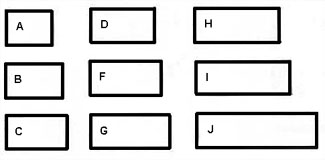

Fechner's Rectangles: Which rectangle is the the most æsthetically pleasing?

Gustav Fechner, an early psychologist, asked 228 men and 119 women which of the following rectangles is æsthetically the most pleasing. Take a look at the following figures. Which figure would you choose?

Fechner's experiment has been repeated with variations in methodology many times and occasionally his results have been supported. In general, the rectangle with the ratio of 21:34 was preferred, with the rectangles adjacent to this one in the picture being rated highly also. The ratio of 21:34 is the so called "golden rectangle" because it's based on the golden ratio or "divine proportion." It's rectangle D above. Euclid defines the golden proportion as

A straight line is said to have been cut in extreme and mean ratio when, as the whole line is to the greater segment, so is the greater to the lesser.

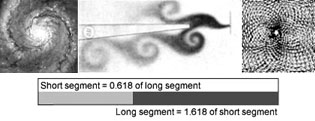

Golden Section, Whirlpool Galaxy; Air Currents from Flue Organ, and Sunflower

Notice in the accompanying figure of the golden section and accompanying examples, how the reciprocal of this ratio involves the same sequence of digits following the decimal point. This ratio is the golden ratio and is ubiquitous in art and nature. Investigators have discovered the golden proportion as the foundational spatial relation in Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa, Salvador Dali's Sacrament of the Last Supper, and numerous other paintings. This number appears in plant and animal growth and has intriguing relationships with architecture and sculpture. The golden section is directly connected with the Fibonacci numbers and the basis of the spiral. Would it be reasonable to conclude, then, that beauty is merely a mathematical relationship?

Or is it more likely that the ubiquitous occurrence of the golden section is just a result of some prosaic numerology and is an example of our ability to manufacture what we want to find by manipulating innumerable numerical relationships which we also create? Moreover, how would these mathematical observations be related to the widespread belief that truly remarkable artists are those who break the rules or laws of past artistic works?

(b) Ethics: the inquiry into the nature and concepts of morality, including the important problems of good, right, duty, virtue, and choice; the study of the principles of living well and doing well as a human being; the moral principles implicit in mores, religion, or philosophy.

As a philosophical problem in ethics, consider this example analyzed by J. O. Urmson in his well-known essay, "Saints and Heroes":

We may imagine a squad of soldiers to be practicing the throwing of live hand grenades; a grenade slips from the hand of one of them and rolls on the ground near the squad; one of them sacrifices his life by throwing himself on the grenade and protecting his comrades with his own body. It is quite unreasonable to suppose that such a man must be impelled by the sort of emotion that he might be impelled by if his best friend were in the squad.[5]

Did the soldier who threw himself on the grenade do the right thing? If he did not cover the grenade, probably several soldiers would be killed. His action undoubtedly saved lives; certainly, an action which saves lives is a morally correct action. One might even be inclined to conclude that saving lives is a duty. But if this were so, wouldn't each of the soldiers have the moral obligation or duty to save his comrades?

Surely this cannot be a correct assessment of the situation because if it were morally obligatory for each one of them to fall on the grenade, each should then have to fight off the others in order to perform his moral obligation to get to the grenade first.

What would you conclude about this example? Would it be our duty to save lives in this situation ceteris paribus, or would we be "going beyond the call of duty" in such a case? Does our right to self-preservation supersede our obligation to save the lives of other persons? Would the number of lives involved in the instance make an ethical difference? What if such an action were to save the world from nuclear destruction?

Admittedly, these brief descriptions and examples do not adequate reflect the nature of philosophy, and they are not especially typical problems. Even so, they are problems intellectually grasped without attendant dangers of confusion by emotional prejudice, and they involve the same sorts of issues as more socially controversial philosophical problems which often involve a plethora of side-issues and persuasive definitions such as euthanasia, genocide, capital punishment, and abortion.

Title Page to Edward Saul's A Historical and Philosophical Account of the Barometer 1735, NOAA Library Collection