Argumentum ad Misericordiam:

Appeal to Pity or Sympathy with Examples

Abstract: The ad misericordiam fallacy illicitly appeals to pity or a related emotion such as sympathy, compassion, or mercy in order to gain the acceptance of an unrelated conclusion. Even so, not all appeals to pity are fallacious. Here, ad misericordiam arguments, both fallacious and nonfallacious, are defined; their structure is shown; and both fallacious and nonfallacious ad misericordia arguments are evaluated with illustrative examples.

Description of ad Misericordiam Arguments

Argumentum ad Misericordiam (argument from pity or misery): the fallacy committed when pity or a related emotion such as sympathy, mercy, or compassion is illicitly appealed to for the sake of getting a conclusion accepted.

- Hence, the fallacy occurs when assent or dissent to a statement or an

argument is sought on the basis of an irrelevant appeal to pity.

- The fallacy can occur in either of two kinds: (1) the appeal to pity

(or a related emotion) is not germane to the conclusion of the argument, or

(2) the enormity of the impassioned appeal is unwarranted given the context

of the argument.

- Generally speaking, in the first fallacious form of the

ad misericordiam argument, the emotional appeal is intentionally

selected to invoke compassion or sympathy in the party to whom the

argument is addressed, but the emotional appeal does not, in itself,

provide relevant evidence for the truth of the conclusion.

For example, consider the following argument from an editorial arguing in favor of establishing a path to U.S. citizenship for undocumented immigrants:“[Texas Senator Ted] Cruz stated his opposition to giving illegal immigrants a path to U.S. citizenship. … I could introduce Cruz to an undocumented immigrant, … [a father who] was afraid to go out to dinner with his kids on Father's Day lest he get stopped by police and deported.”[1]

The father's fear of deportation is not, by itself, a cogent reason he should have a path to citizenship. Instead, the emotion appealed to is a distraction from evidence which could have been adduced.

- Establishing the fallacious nature of the second form of the

ad misericordiam fallacy is sometimes difficult since

the point at which an appeal to pity becomes unwarranted or excessive can

be open to question.

For example, the 19th century forensic legal psychiatrist Isaac Ray argued morally insane persons capable of sound reasoning are not legally responsible for their actions and should be accorded the “dignity and humanity appropriate” for their condition because their “notions of right and wrong are obscured” in the same way as we recognize that “the movements of a new-born infant” are unintentional actions.[2]

Critics argued his justification for not holding morally insane persons legally responsible but holding mentally competent persons legally responsible is an ad misericordiam because Ray's reasoning flouts common sense[3]

- Generally speaking, in the first fallacious form of the

ad misericordiam argument, the emotional appeal is intentionally

selected to invoke compassion or sympathy in the party to whom the

argument is addressed, but the emotional appeal does not, in itself,

provide relevant evidence for the truth of the conclusion.

- Important: Not all appeals to pity are fallacious arguments —

some appeals are appropriate or relevant because the feelings evoked

are logically relevant to the conclusion.

For example, a recommendation to contribute to an organization like Doctors Without Borders on the basis that this group responds to medical emergencies around the world resulting from appalling conflict, disease, and natural disasters would be a nonfallacious appeal. Such an argument provides a legitimate reason to help alleviate humanitarian crises. Thus, feelings of pity or sympathy for unfortunate victims of such disasters are both relevant and appropriate reasons for assistance.

Additional examples of nonfallacious ad misericordiam arguments are provided in Section IV below.

- The fallacy can occur in either of two kinds: (1) the appeal to pity

(or a related emotion) is not germane to the conclusion of the argument, or

(2) the enormity of the impassioned appeal is unwarranted given the context

of the argument.

- A basic schema for the ad misericordiam fallacy is outlined in

the following informal structure:

Guide to the ad Misericordiam Fallacy

Person L asserts statement p or argument A.

L deserves pity because of circumstances y.

[But circumstances y are irrelevant to p or A.]

∴ Statement p is claimed true or argument A is claimed to be good.

- Here's a typical example of this fallacy:

“A candidate for a minor county office in rural Iowa once declared,

‘I have six reasons for your voting for me for the job: Annie, Bobbie,

Charlie, Danny, Esther, and Frankie — my six kids who need financial

support.”[4]

“A candidate for a minor county office in rural Iowa once declared,

‘I have six reasons for your voting for me for the job: Annie, Bobbie,

Charlie, Danny, Esther, and Frankie — my six kids who need financial

support.”[4]

The number of children needing financial support is not a relevant or appropriate job qualification for someone seeking governmental office.

- Hence, the fallacy occurs when assent or dissent to a statement or an

argument is sought on the basis of an irrelevant appeal to pity.

Examples of Ad Misericordiam Fallacies:

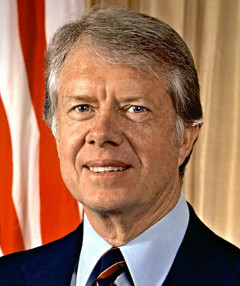

Example 1: In the following passage, pity is sought for a banker who must

sell his stocks in order to be appointed as the Director of the U.S. Office of

Management and Budget:

Example 1: In the following passage, pity is sought for a banker who must

sell his stocks in order to be appointed as the Director of the U.S. Office of

Management and Budget:

“The Georgia Banker [Bert Lance] should be excused from conflict-of-interest divestiture problems, former President Jimmy Carter asserted, because his promise to sell his stock [in order to serve in government] has depressed its market value.”[5]

Comment: President Carter states that we should allow the banker to keep his stock because we should feel sorry for him. Nevertheless, employees of the executive branch of government are required to sell assets in order to avoid either a conflict of interest or the appearance of a conflict of interest. That is, they are not permitted to profit from policies that they might be able to influence as an governmental employee.

Example 2: In the following argument, sympathetic feelings are sought on behalf of a U.S. state governor being tried for corruption:“The jury will begin deliberations tomorrow in the Federal conspiracy and corruption case against Gov. Marvin Mandel of Maryland … Pleading for understanding of Mr. Mandel, Arnold M. Weiner, the Governor's lawyer, said: “After four years of this investigation and two years under indictment, Marvin Mandel is a ruined man. His public life is finished. Every intimate detail of his personal life has been exposed. Even his health and his strength are gone. And nothing you can do can restore it.’”[6]

Comment: The fact that Governor Marvin Mandel's life was made miserable by years of government investigation is not, itself, a valid reason for feeling sympathy for his being charged with corruption.

Example 3: David Cameron, Prime Minister of the U.K. from 2010-2016, states regarding Scottish Independence:“I think that you've heard a lot of arguments that I would call arguments of the head, arguments about whether Scotland would be better off, more prosperous, stronger, safer, inside the United Kingdom or not. … But I think it's also important we make those arguments of the heart … Because I would be heartbroken if this family of nations that we've put together, and that we have done such amazing things together, if this family of nations was torn apart.”[7]

Comment: The speaker's disappointment if Scotland were to become independent of the U.K. is not logically related to the question of whether or not Scotland would be advantaged by independence.

Example 4: A journalist argues that the people who work for the media should not be criticized since many reporters have families, many have lower pay than some other professions, and some been killed in the course of their duties:“The horrible murder of two local journalists in Roanoke, Virginia, has affected me more than I thought it would. … Perhaps this incident will cause some to reconsider the universal denunciation of ‘the media.’ Most reporters have families and many work for lower pay than they might receive in other professions.”[8]

Comment: The writer states that journalists should not be thoughtlessly denounced because they have families and are not well paid. The approval or disapproval of the writings of journalists should not depend upon their family status or their salary level. As well, the substantial distinction between murder and universal denunciation is conflated — the fallacy of ad misericordiam occurs.

Example 5: U.S. Senator Carl Levin testifies concerning Apple Inc.'s practice of tax avoidance:

Example 5: U.S. Senator Carl Levin testifies concerning Apple Inc.'s practice of tax avoidance:

”Many U.S. companies, including Apple, shift intellectual property rights … to offshore affiliates. … The lost tax revenue feeds a budget deficit that has reached troubling proportions … Because of those cuts, children across the country won't get early education from Head Start. Needy seniors will go without meals. Fighter jets sit idle on tarmacs because our military lacks the funding to keep pilots trained.”[9]

Comment: Even though this argument seems plausible, the fallacy of ad misericordiam occurs since Senator Levin argues people suffer because Apple should pay more taxes to help reduce the federal deficit even though Apple is following present tax-laws. One might as well argue that since Congress does not presently address these tax loopholes for various reasons, Congress, itself, is preventing children from getting early education, needy seniors from obtaining meals, and so forth.

Example 6: Addressing the dock, Robert Emment declaims after receiving a death sentence for high treason for leading the ill-timed Irish Uprising of 1803:

Example 6: Addressing the dock, Robert Emment declaims after receiving a death sentence for high treason for leading the ill-timed Irish Uprising of 1803:

“I wish that my memory and name may animate those who survive me, while I look down with complacency on the destruction of that perfidious government, which upholds its dominion by blasphemy of the Most High, which displays its power over man as over the beasts of the forest, which sets man upon his brother, and lifts his hand in the name of God against the throat of his fellow who believes or doubts a little more than the Government standard — a Government steeled to barbarity by the cries of the orphans and the tears of the widows which it has made.”[10]

Comment: In this speech, the excessive emotional appeal with phrases of incisive emotive significance mark this passage as either an ad populum or an ad misericordiam argument concluding that the government is perfidious.

Varieties of Ad Misericordiam Arguments

The ad misericordiam fallacy also occurs when such related emotions such as sympathy, love, regard, mercy, condolence, and compassion are appealed to in order to establish a conclusion whose truth or falsity is not relevant to those emotions.

As seen in fallacy Example 6 above, occasionally, an occurrence of a fallacy can be correctly analyzed as either the ad populum or the ad misericordiam fallacy since these fallacies sometimes overlap in their appeal.

Consider the following example:“In the final moments before Paul Manafort's sentencing Wednesday, the former Trump campaign chief's lawyers appealed for mercy … Convictions for tax and bank fraud, illegal lobbying and witness tampering have been ‘very hard’ on his client, Kevin Downing pleaded in U.S. District Court in Washington on Wednesday. ‘The media attention, the political motivation … is so unreal.’ U.S. District Judge Amy Berman Jackson cut him off. ‘Whose political motivation?’ she asked. ‘Everybody out there,’ he said.”[11]

Manafort's lawyers are requesting mercy in the sentencing because they claim “everybody” has rebuked and has political motives against their client who just happened to break a few laws. So sympathy is sought for very hard effects brought about by “everybody's” attention and for political motivations; hence, the ad misericordiam fallacy is effected by an ad populum argument.

The Ad Misericordiam as a Nonfallacious Argument

Non-fallacious occurrences of the ad misericordiam include arguments where the appeal to pity or a related emotion is the subject of the argument and is a pertinent or germane reason for acceptance of the conclusion.

In the following examples, the appeal to emotions of pity or misery is relevant to establishing the truth or falsity of the conclusion; consequently, these ad misericordiam arguments are not fallacious:

Example 1: Elizabeth Gurley Flynn enumerates some of the reasons she became

a labor organizer:

Example 1: Elizabeth Gurley Flynn enumerates some of the reasons she became

a labor organizer:

“The conditions in the textile towns of New Hampshire and Massachusetts [consisted of] huge gray mills, like prisons, barrack-like company boarding houses, long hours, low wages, long periods of slack … I saw lard instead of butter on neighbors' tables, children without underwear in cold New England winters, a girl scalped by an unguarded machine in a mill across the street from our school. I saw an old man weeping as they put him in the lockup as a tramp. [So] … I became a labor organizer. … I was determined to do something about the bad conditions under which our family and all around us suffered. I have stuck to that purpose for 46 years.”[12]

Comment: No fallacy occurs since her reasons provide relevant evidence for dedicating her life to improving working conditions.

Example 2: Crito tries to convince Socrates to escape from prison:

Example 2: Crito tries to convince Socrates to escape from prison:

“Nor can I think that you are at all justified, Socrates, in betraying your own life when you might be saved … [Y]ou are deserting your own children; for you might bring them up and educate them; instead of which you go away and leave them, and they will have to take their chance; and if they do not meet with the usual fate of orphans, there will be small thanks to you. No man should bring children into the world who is unwilling to persevere to the end in their nurture and education.”[13]

Comment: Crito's appeal to pity or misery is not fallacious: Crito points out the appalling, but relevant, effects of Socrates losing his life.

Example 3: During a 2017 News Conference President Trump states:“[W]e are going to be working very hard on the inner cities, having to do with education, having to do with crime. … You go to some of these inner city places and it's so sad when you look at the crime. You have people — and I've seen this, and I've sort of witnessed it — in fact, in two cases I have actually witnessed it. They lock themselves into apartments, petrified to even leave, in the middle of the day. They're living in hell.”[14]

Regardless of what opinion one has about President Trump's tenure in office, this argument provides relevant reasons for working to improve the condition of inner cites in the U.S. so no fallacy occurs in this passage.

Links to Online Quizzes with Ad Misericordiam

Test your understanding of ad misericordiam and other arguments

with the following quizzes:

Ad Misericordiam Examples Exercise

Fallacies of Relevance I Quiz

Fallacies of Relevance II Quiz

Fallacies of Relevance III Quiz

Informal Fallacy Review

“For … pity … and such passion of the soul, do not pertain to

that matter [modes of persuasion] but relate rather to the juror [or judge]. …

“For … pity … and such passion of the soul, do not pertain to

that matter [modes of persuasion] but relate rather to the juror [or judge]. … For one must not warp the juror by inducing … pity: this would be just as if someone should make crooked the measuring stick he is about to use.”

Rhetoric I.i.1354a (trans. Bartlett)[15]

Notes: Argumentum ad Misericordiam

Hyperlinks go to page cited

1. Ruben Navarrette, “Cruz Finds Redemption,“ Index-Journal 94 no. 19 (May 20, 2013), 6A. Also, here: “There May Be Hope for Cruz on Immigration,” Houston Chronicle (May 19, 2013) Press Reader.↩

2. Isaac Ray, A Treatise on the Medical Jurisprudence of Insanity (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1838), 252, 261. Moral insanity or moral mania is defined in terms of feelings or habits rather than in terms of ethics. The word “moral” in this context (taken from the French language in the early 1800s) could mean emotion as well as moral attitudes. Ray accepted James Cowles Pritchard's definition of “moral insanity” as ”consisting in a morbid perversion of the natural feelings, addictions, inclinations, temper, habits, and moral dispositions, without any notable lesion of the intellect or knowing and reasoning faculties, and particularly without any maniacal hallucination.” [J.C. Prichard, A Treatise on Insanity and Other Disorders Affecting the Mind (Philadelphia: E.L. Carey & A. Hart, 1837), 16.]↩

3. Eric v.d. Luft, “Entry: Isaac Ray” The Dictionary of Early American Philosophers ed. John R. Shook (New York: Continuum, 2012), II:871.↩

4. D. Lincoln Harter and John Sullivan, Propaganda Handbook (Media, PA: 20th Century, 1953), 15.↩

5. William Safire, “Carter's Broken Lance,” The New York Times (July 21, 1977), 23.↩

6. Ben A. Franklin, “Mandel's Case Goes to the Jury; Mercy Is Asked for ‘Ruined Man’,” The New York Times (August 10, 1977), 10. ↩

7. Leon Siciliano, and AFP, video source ITN, ”David Cameron: I Would Be ‘Heartbroken’ If Scotland Leaves the UK” The Telegraph (accessed September 11, 2014).↩

8. Cal Thomas, “Tragedy in Roanoke, ” Index-Journal 97 no. 184 (September 02, 2015), 6A.↩

9. Carl Levin, “Statement of Senator Carl Levin (D-Mich) U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations on Offshore Profit Shifting and the U.S. Tax Code” U.S. Senate Committee Homeland Security & Governmental Affairs (May 31, 2013) (accessed March 3, 2021).↩

10. John W. Burke, Life of Robert Emmett: the Celebrated Irish Patriot and Martyr 3rd. ed. (Philadelphia: Thomas, Cowperthwaite, 1852), 134.↩

11. Dana Milbank, “Manafort's Lawyers Appealed for Mercy — But Not from the Judge,” Index-Journal 100 no.365 (March 16, 2019), 9A. Also online here: Dana Milbank, “Manafort's Lawyers Appealed for Mercy — But Not From the Judge,” The Washington Post (March 13, 2019) (accessed January 28, 2022).↩

12. Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn Speaks to the Court (New York: New Century, 1952), 6. Also Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, “Statement at the Smith Act Trial” American Rhetoric (April 24, 1952).↩

13. Plato, Crito 45c-d, trans. Jowett.↩

14. Donald Trump. “Full Transcript: Trump News Conference,” The New York Times (February 16, 2017). Although no fallacy occurs, what former president Trump witnessed or saw is not clearly stated.↩

15. Aristotle, Aristotle's Art of Rhetoric trans. Robert C. Bartlett (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019), 6.↩

Relay corrections or suggestions to philhelp@philosophy.lander.edu

Read the disclaimer concerning this page.

1997-2023 Licensed under GFDL

and Creative

Commons 3.0

The “Copyleft” copyright assures the user the freedom to use,

copy, redistribute, make modifications with the same terms.

Works for sale must link to a free copy.

The “Creative Commons” copyright assures the user the

freedom

to copy, distribute, display, and modify on the same terms.

Works for sale must link to a free copy.