Plato's The Apology Part I

Philosophy of Life

February 19 2026 03:10 EST

Socrates,

adapted from Cooper,

Life of Socrates

Library of Congress

LC-USZ61-1501

Plato's The Apology Part I

Abstract: Plato's account of Socrates' trial elucidates some main principles of the Socratic philosophy: (1) the Socratic paradox, (2) the Socratic method, (3) tending ones soul, and (4) death is not to be feared.

The reading for these questions is found here in PDF form: “Just Do What's Right,” by Plato

- What are the specific charges brought against Socrates, and why do you think he was so charged? Is Socrates being charged with being a sophist? Is he being accused of offering scientific explanations for religious matters?

- Why doesn't Socrates plead for a lesser charge? Why couldn't he accept exile?

- How does Socrates show that he does not corrupt the young people of Athens? Are his arguments convincing?

- Explain Socrates' defense of his belief in God. How persuasive do you find it?

- What is Socrates' philosophy of life? Why has it been called paradoxical?

- Explain why Socrates compares himself to a "gadfly." What does he mean when he uses this term?

- Notes are arranged in response to the questions from Plato's

Apology Part I also available in HTML:

Chapter 4: “Just Do What's

Right”

- Answers from the chapter beginning (HTML form):

Chapter 4: “Just Do What's

Right” in Reading for Philosophical Inquiry, Version 0.21.

- What are the specific charges brought against Socrates,

and why do you think he was so charged? Is Socrates being

charged with being a sophist? Is he being accused of

offering scientific explanations for religious matters?

- At the heart of this question is the Socratic Problem: since Socrates apparently wrote nothing, his manner and philosophy are subject to the controversy of conflicting accounts. The historical problem of Socrates is omitted in these notes. The presentation of the Socrates described by Plato is assumed here in part because of Aristotle's testimony that Socrates concerned himself with "the excellences of character" and the attempt to find the essences of ethical terms. Even so, how much of the thought in the Socratic dialogues is Plato's is a matter of debate as well.

- Summary of the charges against Socrates:

- Impiety: he does not believe in the gods whom the state believes in—he seeks natural explanations for natural processes

- He teaches people to disbelieve the gods—a charge suggested in Aristophanes' play Clouds, Socrates is portrayed as an atheist.

- He corrupts the young; he infuses in them a spirit of criticism—Socrates did attract attention from wealthy young men in Athens as he cross-examined prominent citizens in the marketplace. It's quite possible he occasionally accepted some support from them. In his examination of statesmen, poets, and artisans, he reveals that they do not know what they claim to know. In any case, by his questioning of authority, he had an effect on the young.

- He is a wrongdoer; he speculates about the heaven and things beneath the earth—perhaps this is the basis of the charge of disbelief in the gods if Socrates seeks natural explanations for astronomical and geological phenomena rather than attributing natural events to the gods. Early in his life Socrates apparently was interested in science; later in life Socrates emphasized ethical and epistemological inquiry.

- He makes the weaker reason seem to be the stronger—Socrates here is being accused of being a sophist. Aristophanes' play Clouds some thirty-five years earlier had portrayed Socrates as a sophist.

- Originally the sophists were known as the Seven

Sages of Greece, but later the term "sophist" was

applied in a derogatory sense to persons who made their living

teaching methods of wining lawsuits in the courts. Again,

Aristophanes' play had portrayed Socrates as a teacher or

rhetoric and astronomy.

- The sophists were itinerate teachers who were the encyclopædists, the polymaths, who knew a little about everything—in general, they were skeptical with regard to ethics and knowledge.

- Unlike philosophers, they took payment for their

teaching and were accused of "corrupting the youth."

Brief examples of sophistical arguments include:

- Your fourth finger is longer than your little finger but shorter than your middle finger. Thus, a finger is both long and short.

- Here is proof that you are on the other side of campus. Do you know where the Bell Tower is? Well, then you know that you are on the other side of campus from the Bell Tower.

- Consider the well-known story of Euthalus and Protagoras.

Euthalus wanted to become a lawyer but could not pay Protagoras.

Protagoras agreed to teach him under the condition that

if Euathlus won his first case, he would pay Protagoras,

otherwise not. Euathlus agreed and finished his course of study

and but did enter the courts. Protagoras sued for his fee.

- Protagoras argued: If Euathlus loses this case, then he must pay (by the judgment of the court). If Euathlus wins this case, then he must pay (by the terms of the contract). He must either win or lose this case. Therefore Euathlus must pay me.

- But Euathlus had learned well the art of rhetoric. He responded: "If I win this case, I do not have to pay (by the judgment of the court). If I lose this case, I do not have to pay (by the contract). I must either win or lose the case. Therefore, I do not have to pay Protagoras."

- Why doesn't Socrates plead for a lesser charge? Why

couldn't he accept exile?

- Socrates' understanding of himself is that life is not worth living is he cannot choose what is right (c.f., the Socratic paradox.)

- Socrates notes that he cannot change and improve his soul; hence, if he went elsewhere, he would continue his questioning. Citizens of other city-states would probably tolerate his questionings even less well than his fellow Athenians. Undoubtedly, he would be continually expelled or worse.

- Undoubtedly the lack of compromise on principles by Socrates led to the court condemning him to death by a greater margin than when voting for his guilt.

- Socrates claims that he is following the god's order to examine his fellow citizens. Chærephon asked the Delphic Oracle if there were any man living who was wiser than Socrates. The Oracle answer was "No." Yet, Socrates did not see himself as being wise, so through questioning of others, he realized the basis of the Oracle's statement of his wisdom was that he knew that he did not know and so his life mission was, in effect, to prove the Oracle's assertion. (Cf., Socratic irony in Part II of these notes.)

- How does Socrates show that he does not corrupt the young

people of Athens? Are his arguments convincing?

- Socrates' answer to this charge, more than any other, exhibits the courtroom tactics of a sophist. A.E. Taylor suggests that Socrates does not take these charges seriously and exhibits the often observed irony as he plays with his accusers.

- Socrates states that the charge of corruption of the youth is a "stock charge" against all philosophers. The charge may well be common against sophists, but such a defense is irrelevant to Socrates' situation. The relevant question is not the ad hominem but is rather whether or not the charge is true in this case.

- Socrates professes ignorance: he states that he knows nothing so how could he possibly teach the young people anything? If somehow a young person were corrupted, then the corruption was unintentional. Many commentators including A.E. Taylor see Socrates' stance as part of the doctrine "no one does evil volunta1rily." Yet, this is an odd defense for Socrates to make, since, as a result of the Socratic Paradox, Socrates believes we are morally responsible for knowledge or the lack thereof. An unintentional action results from ignorance, and a person is responsible for what is not known.

- Finally, Socrates states the ad

ignorantiam argument that there is no one present testifying

that he was corrupted. In a court of law, of course, there is the

burden of proof on the prosecution, and evidence or testimony need

be offered for those charges. But from a logical point of view,

Socrates' argument is the ad ignorantiam fallacy:

- No proof has been placed into evidence that anyone has been corrupted.

- --------------------------------------------------

- Therefore, no one has been corrupted.

- Socrates proposes the following dilemma:

- If I drive away the young men, they will persuade their parents to expel me.

- If I allow them to stay, their fathers will expel me [on account of the influence on their sons].

- [Either I drive them away or I allow them to stay.]

- ------------------------------------------------------

- Thus, either they will persuade their parents to expel me or their fathers will expel me.

- The use of the dilemma is in a sense a sophistic rhetorical

device which is effective in a courtroom but of little logical

significance. Let's spend a moment analyzing the dilemma. There

are three ways to refute a dilemma:

- Take it by the horns: i.e., show that at least one of the conditionals is false. For example, if Socrates drives the young men away, it's unlikely they could induce their parents to expel him.

- Escape between the horns: i.e., show that the disjunction is false. For example, Socrates could not control whether or not the young men stay and listen.

- Set up a counter-dilemma: negate the consequents of

the conditionals and switch them for new conditional statements.

Then draw the conclusion as in the following argument:

- If I drive away the young men, their fathers will not expel me.

- If I do not drive them away, they won't persuade their parents to expel me.

- [Either I drive them away or I allow them to stay.]

- ------------------------------------------------------

- Thus, either their fathers will not expel me or they won't persuade their fathers to expel me.

- Explain Socrates' defense of his belief in God. How

persuasive do you find it?

- First, Socrates simply points out the contradiction between the two groups of accusers: he can't be an atheist and at the same time believe in false gods. But, of course, this response does not address the emotional effect of the charge of impiety.

- Second, Socrates presents the linguistic argument that if he believes in divine things, then he cannot be an atheist. Since there is evidence for the antecedent of the conditional, the truth of the consequent does follow.

- Socrates does not address philosophical reasons for his belief in the gods; he merely demonstrates the errors in the prosecution's charges.

- What is Socrates' philosophy of life? Why has it been

called paradoxical?

- A number of statements in the Apology point to the

heart of the Socratic philosophy: the Socratic

Paradox.

- Socrates states at the beginning of his defense: "Give your whole attention to the question, is what I say just, or is it not?"

- He believes that you should only do what's right—irrespective of matters of life or death. (Socrates later offers a proof that no harm can come to a good person and death is not to be feared.)

- Your life should be spent on the improvement of your soul.

- Socrates states, "[I]f I say again that daily to discourse about virtue, and of those other things about which you hear me examining myself and others, is the greatest good of man, and that the unexamined life is not worth living, you are still less likely to believe me." (Apology, 38a, trans. Benjamin Jowlett).

- The Socratic Paradox: People act immorally, but they do

not do so deliberately.

- Everyone seeks what is most serviceable to oneself or what is in ones own self-interest.

- If one [practically] knows what is good, one will always act in such manner as to achieve it. (Otherwise, one does not know or only knows in a theoretical fashion.)

- If one acts in a manner not conducive to ones good, then that person must have been mistaken (i.e., that person lacks the knowledge of how to obtain what was serviceable in that instance).

- If one acts with knowledge then one will obtain that which is serviceable to oneself or that which is in ones self-interest.

- Thus, for Socrates…

- knowledge = [def.] virtue, good, arete

- ignorance = [def.] bad, evil, not useful

- Since no one knowingly harms himself, if harm comes to that person, then that person must have acted in ignorance.

- Consequently, it would seem to follow we are responsible for what we know or for that matter what we do not know. So, then, one is responsible for ones own happiness.

- The essential aspect of understanding the Paradox is to realize that Socrates is referring to the good of the soul in terms of knowledge and doing what's right—not to wealth or freedom from physical pain. The latter play no role in the soul being centered.

- Examples of the Paradox explained in practice.

- Cheryl and her friend Holly, both twelve years old decide to

go to the movies. Cheryl, unlike her friend Holly, states

that she is eleven so that she will not have to pay the adult

admission and will have extra money for snacks. Holly refuses

to do so since her parents have told her that if she cannot

pay the admission of a twelve year old, then she doesn't have

enough money to go the movies.

- Cheryl gives Holly some of her extra snacks as a way of showing Holly that Holly made a foolish decision.

- If we were to ask Cheryl if she made the right decision, she would happily say, "Yes, of course!" If we were to ask Holly if she made the right decision, Holly would perhaps glumly say, "Yes, I did the right thing."

- Cheryl lacks knowledge of the longer-term effect on her soul; Holly lacks knowledge of the rightness of following her parents' advice.

- Consider the effects of a choice like Cheryl's on her soul

in the longer term. She might…

- Lack an authentic self: Compare Cheryl's development of different personalities for different people to Socrates' being the same before the court as he was in the marketplace.

- Seek an edge: What becomes fair to Cheryl are those circumstances where she has an advantage. Cheryl comes to believe a level playing field is unfair to her. She does not interact unless she has an advantage.

- Consequently feel guilt or even pride: Cheryl came to believe that she is better or smarter than other people because she can play by different rules. In other cases, some persons like Cheryl might feel guilt for not doing the right thing.

- Reject conditions for fair-treatment: At the age of fourteen, when Cheryl was asked for evidence of her age by a movie ticket-seller she became angry, saying, "I was admitted last week as child—you just don't get a whole year older in one week!"

- Lose confidence or self-esteem: Cheryl learns to only feel comfortable when she has an advantage. Without an advantage, she feels at a loss.

- Be left to improvise in new situations: By cutting corners or seeking

the advantage, in new situations, the soul is out of balance

because of the attempt to avoid being treated as others

are. As Sir

Walter Scott wrote,

"O what a tangled web we weave, When first we practice to deceive!"

- Have a soul not centered: By having to foresee future circumstances dependent upon what she has done in the past, her attention becomes scattered among calculating different scenarios.

- Cheryl and her friend Holly, both twelve years old decide to

go to the movies. Cheryl, unlike her friend Holly, states

that she is eleven so that she will not have to pay the adult

admission and will have extra money for snacks. Holly refuses

to do so since her parents have told her that if she cannot

pay the admission of a twelve year old, then she doesn't have

enough money to go the movies.

- A number of statements in the Apology point to the

heart of the Socratic philosophy: the Socratic

Paradox.

- Explain why Socrates compares himself to a "gadfly."

What does he mean when he uses this term?

- A gadfly is a fly that stings or annoys livestock; hence one that acts as a provocative stimulus.

- Socrates is trying to arouse drowsy, apathetic people to realize that they do not know themselves and do not know what they claim to know. Socrates' cross-examination of the some of the prominent citizens undoubtedly led to prejudice against him.

- Consider Plato's dialogue the Theætetus as

an example of Socrates' stinging: he questions Theætetus, a

well-known mathematician, as to the nature of knowledge.

- Theætetus explains knowledge as perception. (Protagoras had

argued that "Man is the measure of all things.")

- If that be so, Socrates asks, how Protagoras can rank his knowledge over that of other men.

- If knowledge were the same as perception, then hearing a foreign language would be the same as understanding it.

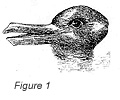

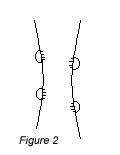

We can perceive without knowing what we are

perceiving. Note Figure 1 the well-known duck-rabbit

figure from Gestalt psychology or Figure 2 Norwood Russell

Hanson's "bear climbing a tree."

We can perceive without knowing what we are

perceiving. Note Figure 1 the well-known duck-rabbit

figure from Gestalt psychology or Figure 2 Norwood Russell

Hanson's "bear climbing a tree." If knowledge were the same as perception, as soon as we

cease to perceive, then we would cease to know—but

this is not the case.

If knowledge were the same as perception, as soon as we

cease to perceive, then we would cease to know—but

this is not the case.- We can know some things without perceiving them (i.e., truths of mathematics, a telephone number).

- Theætetus' second attempt: knowledge is true opinion.

- Socrates' objection: an opinion can be true without involving knowledge—the opinion might just be coincidental with the truth

- Consider a murderer on trial: In the face of inadequate evidence the jury might vote "guilty," and by luck, the opinion turns out to be correct. Even so, we would not say the jury had knowledge at the time they returned their verdict.

- Theætetus' third attempt: knowledge is true opinion plus

explanation or an account. I.e., if something cannot be

analyzed, it cannot be known.

- Socrates notes if explanation means analyzing into elements of differentia, then we cannot have knowledge, for the results of analysis are themselves unanalyzable.

- Therefore, the unknowable is reduced to what cannot be known.

- The final result of the dialogue is not a completely a negative result because Socrates has shown by implication that knowledge must somehow involve the intelligent grasping of the structure and relationships of a thing.

- Theætetus explains knowledge as perception. (Protagoras had

argued that "Man is the measure of all things.")

- What are the specific charges brought against Socrates,

and why do you think he was so charged? Is Socrates being

charged with being a sophist? Is he being accused of

offering scientific explanations for religious matters?

- Notes on Plato's Apology are continued in Part II of these notes. Part II emphasizes Socrates' response to the verdict.

- Answers from the chapter beginning (HTML form):

Chapter 4: “Just Do What's

Right” in Reading for Philosophical Inquiry, Version 0.21.

- Further Reading:

“You are mistaken, my friend, if you think that a man who is worth

anything ought to spend his time weighing up the prospects of life and

death. He has only one thing to consider in performing any action—that

is, whether he is acting rightly or wrongly, like a god man or a bad

one.”

Plato, Socrates' Defense (Apology) trans. Hugh Tredennick in

Plato: The Collected Dialogues (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press, 1961), 28b.

Relay corrections or suggestions to philhelp@gmail

Read the disclaimer concerning this page.

1997-2025 Licensed under GFDL

and Creative

Commons 3.0

The “Copyleft” copyright assures the user the freedom

to use,

copy, redistribute, make modifications with the same terms.

Works for sale must link to a free copy.

The “Creative Commons” copyright assures the user the

freedom

to copy, distribute, display, and modify on the same terms.

Works for sale must link to a free copy.